The phrase “release the Epstein files” has such rhetorical power because it promises moral clarity. It offers the public a cathartic moment, exposure, accountability, a sense that the powerful can’t hide behind the system.

And in a political culture that increasingly treats outrage as both a pastime and a strategy, it can feel especially satisfying: like we’re sticking it to our opponents and shaking loose a network of predators.

But the pleasure should instead signal a warning light.

The bigger danger in an all-at-once “files” release isn’t that we’ll learn something uncomfortable about famous people. It’s that we’ll further damage the one thing a society cannot function without: credible trust in the rule-of-law process, law enforcement, prosecutors, courts, and the professionalism that makes those institutions something other than weapons.

If our standard for justice becomes “dump everything and let the internet sort it out,” we are not strengthening accountability. We’re degrading it into a spectacle.

The process is the point

We’ve built a serious, rights-protecting system over many decades because we learned, often the hard way, that justice is fragile.

It requires rules. It requires restraint. It requires a chain of custody, evidentiary standards, defense rights, judicial oversight, and accountability mechanisms that are boring precisely because they are meant to be fair.

That system is not perfect. But it’s the only system designed to produce outcomes that can be defended as legitimate rather than simply popular.

Trust in a fair process is hard to build and easy to shred

When people demand wholesale disclosure “so we can finally know,” they often mean well. Yet what they’re really signaling is that they no longer believe the system is capable of doing its job.

And once that belief collapses, every outcome becomes suspect, every indictment “political,” every acquittal “corruption,” every redaction a “cover-up,” and every delay “protection of the guilty.”

Trust in a fair process is hard to build and easy to shred. And it is being shredded, conveniently, profitably, relentlessly, by partisan actors who gain power by teaching the public to sneer at institutions. In this sense, the Trump Administration’s abuse of the Department of Justice is doing long-term damage to America’s political health.

Raw disclosure is not truth. It’s noise.

One of the most underappreciated facts in this debate is scale. These “files” aren’t a single dossier or a neat case folder. They’re sprawling: tips, leads, hearsay, partial recollections, contact information, interview notes, procedural artifacts, and the messy exhaust of investigative work.

Even if you believe every page should ultimately be available in some form, the idea that the public can responsibly “synthesize” a multi-million-page trove is fantasy.

That’s not an insult to the public; it’s a description of what investigation is. It is confusing by nature. It includes contradictions. It includes false leads. It includes information that is true but misleading without context. It includes names that are incidental, not incriminating.

A mass release turns investigatory material into a public scavenger hunt, where the loudest interpretation wins, and where “being mentioned” becomes “being guilty"

The proper place to assess this kind of material is inside a professional justice system, where trained investigators and prosecutors can evaluate credibility, corroborate claims, discard dead ends, protect victims, and bring charges only when evidence and law justify it.

A mass release does the opposite. It turns investigatory material into a public scavenger hunt, where the loudest interpretation wins, and where “being mentioned” becomes “being guilty.”

As Jay Daniel Thompson points out in Religion & Ethics, conspiracies can become political weapons and don’t necessarily increase understanding; they can obscure victims’ suffering and turn everything into a factional spectacle.

The due process problem: reputations, victims, and irreversible harm

In a courtroom, allegations are filtered. Evidence is tested. Claims face cross-examination. Judges enforce rules. Defendants can respond. That structure protects society from mob justice and protects individuals from being destroyed by rumor.

A raw dump doesn’t just “increase transparency.” It sidesteps constitutional and ethical safeguards that exist for good reason. One predictable result is that people who have never been charged can be permanently smeared.

A single line, phone number, or ambiguous reference, stripped of context, can be spun into viral “proof” for whatever narrative is most convenient

Investigatory files often include incidental contacts, dead-end tips, or allegations that never met the evidentiary threshold. Once a name starts circulating online, any correction—if it comes at all—usually comes too late.

This kind of disclosure can also expose victims and witnesses and invite bad actors to weaponize stray details. A single line, phone number, or ambiguous reference, stripped of context, can be spun into viral “proof” for whatever narrative is most convenient.

Social media and conspiracy ecosystems only accelerate that dynamic. In the end, it encourages punishment without adjudication.

We’ve seen this movie: disclosure doesn’t satisfy conspiracy

The promise of disclosure is that it will settle the matter. But the psychology of conspiracy doesn’t work that way. The hunger is not for truth; it’s for fuel.

We have a modern case study in the enduring obsession with the JFK assassination: document releases didn’t end the conspiracies; they generated new ones. Each tranche produced fresh omissions, fresh interpretations, and fresh micro-mysteries to inhabit forever.

President Trump finally released all the CIA JFK files in 2025, and we got…nothing

President Trump finally released all the CIA JFK files in 2025, and we got…nothing

President Trump finally released all the CIA JFK files in 2025, and we got…nothing. Aside from undercutting the professional standards that help protect intelligence collection, we learned nothing at all. Transparency, in other words, didn’t cure suspicion; it accelerated it.

The same dynamic is guaranteed here. If the release is partial, people will insist the withheld portions are the real story. If it’s heavily redacted, the black bars will become the story. If it’s complete, the sheer volume will ensure cherry-picking never ends.

As Benjamin Wittes commented in his Lawfare article, No, Don’t Release the Epstein Files, “You cannot sate the conspiracy beast with disclosure. Its appetite is totally unquenchable.”

This isn’t abstract for me. I host a podcast about conspiracy theories—Mission Implausible—with a former CIA colleague. Our entire premise is that raw claims, severed from context, can metastasize into certainty in the public imagination.

That effect is amplified when political leaders flirt with conspiracism, elevate it, and use it as a governing style. When leaders treat truth as tactical, “release the files” becomes less a commitment to justice than a move in an information war.

A useful analogy: intelligence “dots” aren’t conclusions

My experience in the intelligence community also provides useful context. The intelligence world and the justice system are different, but they share a core lesson: raw inputs are not finished products.

In intelligence, you collect enormous amounts of reporting, often fragmentary, sometimes wrong, and occasionally deceptive. Good organizations treat those “dots” as leads, not conclusions.

Validation happens in layers: you evaluate sources, then test specific claims, weigh competing explanations, synthesize what holds up, and clearly state any remaining uncertainty. The discipline isn’t just about acquiring information; it’s about stress-testing it, again and again.

When people push to dump investigatory material into the public square, they aren’t advancing truth

That’s why one classic mistake, made by observers, journalists, politicians, and even well-intentioned bureaucrats, is treating the existence of a report as proof. A raw report is not the collector vouching for a claim’s truth; it’s the collector saying, “This is what a source reported.” Truth-testing comes later.

I wrote about this hazard when assessing the misnamed Steele Dossier. The rush to treat raw reports as settled conclusions led to dangerous misunderstandings.

You’d think the Trump administration would have learned that lesson, given how central it is to their narrative of victimhood.

The justice system is even stricter because it must be. Intelligence can live with probabilities. Courts must live with evidence. So, when people push to dump investigatory material into the public square, they aren’t advancing truth. They’re confusing “having the dots” with “drawing the conclusion.”

The false thrill of accountability

There is also something emotionally seductive about mass exposure: it feels like accountability without the waiting, the uncertainty, the slow grind of institutional work. But it’s counterfeit.

Real accountability has a stamp: charges where warranted, trials with rules, verdicts that can withstand scrutiny, sentencing in the open, and appeals that protect against error.

What a data dump produces is performance accountability, a chaotic, politicized theater

What a data dump produces instead is performance accountability, a chaotic, politicized theater where reputations are destroyed by insinuation, where victims become collateral, and where the loudest faction gets to declare victory.

In such a situation, it is hard to distinguish transparency from voyeurism. And in the end, it leaves us worse off: angrier, more suspicious, less confident that there is any neutral process at all.

A fragile system we all rely on

It’s tempting to see this as a special case: Epstein was monstrous; therefore, normal rules don’t apply. That instinct is understandable and dangerous.

Once we decide that process is optional when the target is sufficiently hated, we’ve set a precedent that will be used again, and not only against monsters - John Sipher

Once we decide that process is optional when the target is sufficiently hated, we’ve set a precedent that will be used again, and not only against monsters - John Sipher

Once we decide that process is optional when the target is sufficiently hated, we’ve set a precedent that will be used again, and not only against monsters.

Due process isn’t a gift to the guilty. It’s the architecture that protects the innocent, limits further harm to victims, and prevents politics-by-allegation from substituting for evidence.

If we trade that architecture for partisan gratification, we won’t strengthen justice; we’ll weaken the system that makes justice possible. We should demand more institutional seriousness, not less.

And if we care about victims, we should care about preventing the next wave of exploitation.

And when the next scandal arrives, and there will always be a next scandal, we will have less capacity to resolve it legitimately and more incentive to settle it as a factional brawl.

That is the deeper danger of “releasing the Epstein files.” It may feel politically satisfying, but it reflects a collapse of trust in our institutions. It doesn’t just reveal what’s inside the documents. It reveals what’s happening to us.

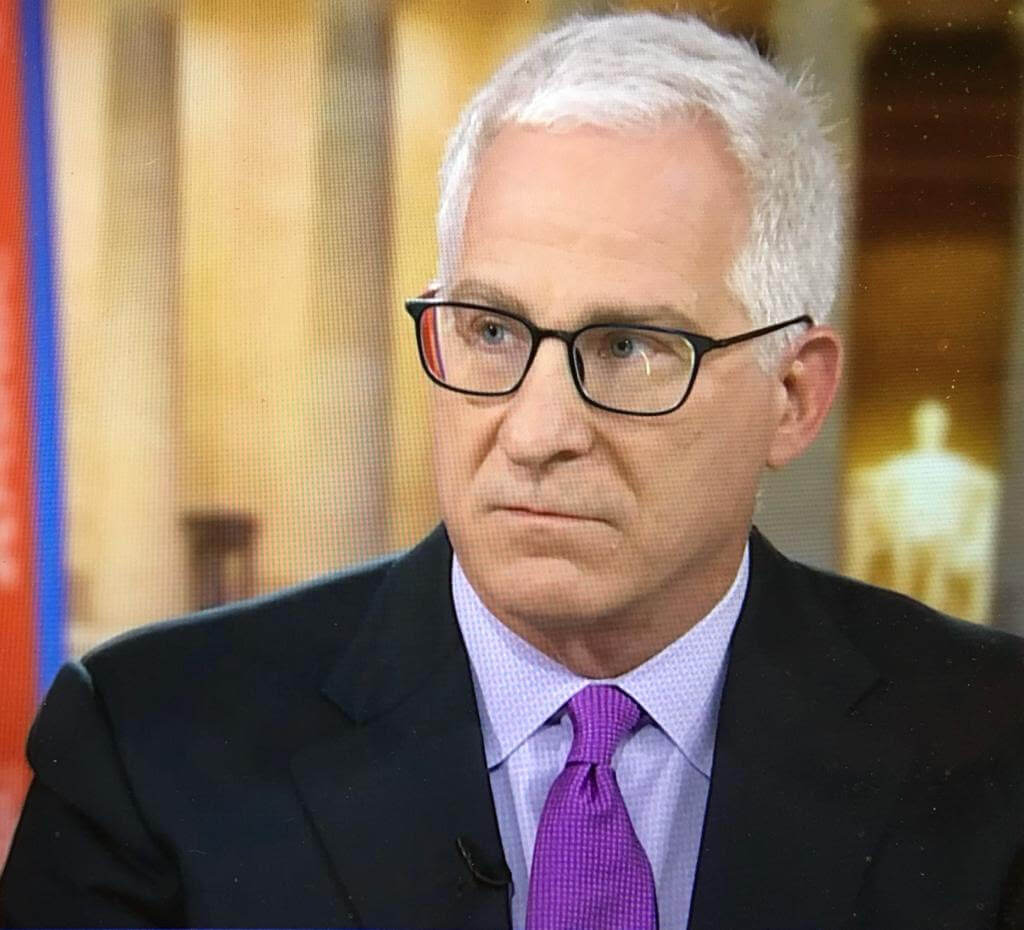

John Sipher ( @johnsipher.bsky.social ) is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and co-founder of Spycraft Entertainment. He worked for the CIA’s Clandestine Service for 28 years and is the recipient of the Agency’s Distinguished Career Intelligence medal. He is also a host and producer of the "Mission Implausible" podcast, exploring conspiracy theories.