China's political system does not handle personnel changes as democracies do. It does not provide public indictments with details, conduct open discussions, or present evidence before the cameras.

Instead, it sends signals. Sometimes it is an absence from an event, sometimes a sudden personnel change, and sometimes a phrase is used in the exact manner the Party prefers, where the message is understood but not the content.

On 24 January, such a signal was sent at the highest level: China's Ministry of Defence announced that General Zhang Youxia, Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), the highest body governing the armed forces, and General Liu Zhenli, Chief of Staff of the Joint Staff Department of the CMC (the operational command centre), were under investigation.

The standard phrase "serious violations of discipline and law" was used in the announcement. In the Chinese system, this type of phrase is not a legal definition for the public but a political signal.

It shows that the issue is serious enough to be public, but it doesn't say what's at stake or who may ask questions.

Political control and the culture of command

The fact that the Vice Chairman of the CMC is named changes the scale of the issue. The CMC sits at the top of the pyramid above the People's Liberation Army (PLA), which represents the armed forces in their broadest sense.

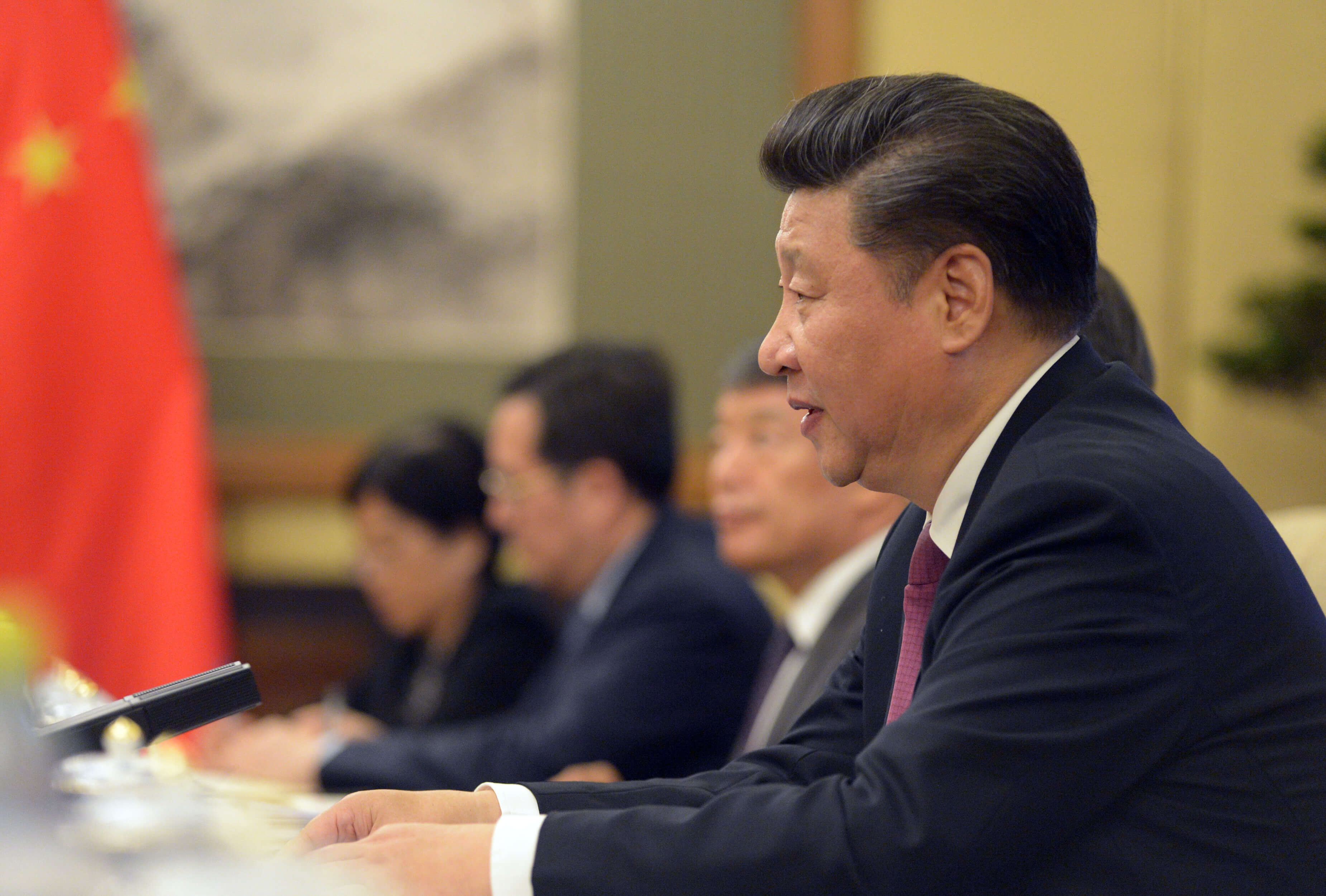

The Chairman of the CMC is Xi Jinping, who is also the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and President of the of the People's Republic of China.

The vice-chairmen of the CMC are the closest institutional pillars of this system. When such a figure becomes the subject of an investigation, it is not merely an "anti-corruption action". It is a blow at the very top of the mechanism that controls the military.

An explanation that reduces the issue to "consolidation of power" overlooks a more significant aspect of the problem. In China, centralised political power is a permanent condition.

What requires attention is how these actions affect the military apparatus, which must simultaneously modernise, accelerate decision-making, and maintain its ability to operate in high-risk conditions.

The message is not intended only for the two generals; it is directed at the entire system

Military modernisation involves more than just the production of new ships, aircraft, and missiles. Modernisation is also a culture of command. It involves trust in the chain of responsibility. It is the willingness to make quick decisions at lower levels, with a clear understanding of authority and consequences.

In a system that rewards discipline and loyalty, that culture can function, but only as long as there is a balance between political control and professional initiative.

Shifting this balance leads to an institutional effect in which decisions are increasingly made through administrative filters and less often through professional military judgement.

This reduces the flexibility of command and slows the system’s response. It is precisely here that the essence of the current wave should be sought.

The message is not intended only for the two generals; it is directed at the entire system, from the general staff offices to the command posts in the fleets, air force, and missile forces.

The moment the leadership signals that no one is beyond the scope of investigation, the lower levels instinctively increase their caution.

Caution is a rational response in a system where consequences are not always clearly defined by law but are politically assessed. When caution becomes the dominant mode of operation, speed and flexibility decline.

When discipline means loyalty, not just law

For readers outside China, it is important to understand the term "discipline". Discipline in Chinese political terminology encompasses more than merely following rules and laws.

Discipline also means political conformity, behaviour in accordance with party expectations, loyalty in assessment, tone in public, selection of personnel, use of the budget, attitude towards military suppliers, and even communication style.

When the phrase "serious violations of discipline and law" is used, it leaves room for the subject to be corruption, abuse of position, networks of influence perceived as autonomous, or decision-making that has exceeded the limits of permissible self-confidence.

China has publicly confirmed cases involving the removal of high-ranking military personnel and officials

Therefore, this cannot be considered an isolated case. In the past few years, China has publicly confirmed cases involving the removal of high-ranking military personnel and officials related to the defence sector, including former defence ministers.

The pattern is clear: the system strikes where three things converge – money, technology, and power. The military, particularly in procurement, consistently connects these three elements.

Whoever manages procurement also manages channels of influence. Whoever manages the channels of influence also influences personnel. Whoever influences personnel can create parallel loyalties that the Party does not tolerate.

When fear of responsibility shapes command

There is an aspect of this process that is often overlooked. The removals and investigations at the top of the command are not merely a matter of personnel "purge" but a means of redefining acceptable risk within the military system.

China cannot allow its military to be politically out of step with the party leadership. At the same time, it cannot accept an army whose actions are hampered by fear of responsibility.

One of the most complex challenges facing China's leadership today is reconciling these two demands simultaneously.

If the campaign is genuinely a fight against corruption in defence procurement, the consequences can be positive: less financial leakage, improved quality control, and stronger standards.

However, if the campaign in practice becomes a method of constant discipline through uncertainty, the consequences can be the opposite: people will avoid responsibility, fewer decisions will be signed, bad news will be suppressed, and innovations will be forced into formal frameworks that slow down the system.

The regime increases control to boost efficiency but ends up reducing the apparatus's ability to react freely and quickly

This paradox recurs repeatedly in authoritarian states: the regime increases control to boost efficiency but ends up reducing the apparatus's ability to react freely and quickly.

When this translates into military reality, very specific effects emerge. Procurement slows, as every contract is considered a potential risk. Defence companies became more cautious, knowing that the political climate could change without warning.

The middle level of command becomes prone to formalism, because it offers protection. People begin to choose "safe" decisions, even when they are operationally weaker. Mistakes are less likely to be acknowledged, as any admission may be interpreted as weakness or ill will.

An army that is loyal—but slower

This brings us to the question of international consequences. The West often views the Chinese military through two extremes: either as an unstoppable machine rapidly modernising or as a corrupt apparatus unable to withstand a serious test.

The reality, as usual, is more complex. China has the resources and industrial base to rapidly update equipment and technology. However, the capability for complex operations depends more on command culture than on the number of platforms.

If an atmosphere is created at the top of the military in which political security takes precedence over professional discussion, this may strengthen central control in the short term but reduce the quality of crisis decisions in the long term.

This is precisely why this case should be viewed as a risk management issue, not merely as a personnel change. Beijing clearly wants to eliminate the possibility of the military leadership being beholden to anyone but the Party.

The investigation into Zhang Youxia and Liu Zhenli is not merely an internal matter of discipline

Changes at the top of the command have immediate consequences for decision-making and internal coordination. Managing these effects is one of the key challenges of the Chinese military system.

There is another crucial dimension to understand. Military power is not just the ability to act; it is also the ability to threaten convincingly while maintaining control over escalation.

For the threat to be convincing, the command system must be reliable, stable, and predictable. For escalation control to be sustainable, decision-making must include enough professional voices to warn of consequences.

When the decision-making circle is too narrow, the risk of misjudgement increases.

In this context, the investigation into Zhang Youxia and Liu Zhenli is not merely an internal matter of discipline. It signals that China is entering a phase in which it seeks to redefine the relationship between the Party and the military amid accelerated modernisation.

Careful management of this redefinition could enable China to achieve a military that is both loyal and effective. If handled too crudely, however, China may end up with an army that is loyal but slower, more cautious, less flexible, and prone to formalism at a time when initiative and speed are needed.

Operational capability or bureaucratic strength

The most important question for the coming period is not who will be targeted next, but what kind of command culture the Party actually intends to foster.

The most important question for the coming period is not who will be targeted next, but what kind of command culture the Party actually intends to foster - Xi Jinping

The most important question for the coming period is not who will be targeted next, but what kind of command culture the Party actually intends to foster - Xi Jinping

Does it want officers who make decisions based on the mission or those who decide according to their own assessment of political risk?

The difference between these two types of officers is the difference between operational capability and bureaucratic strength.

In China, therefore, there is no "purge" in the sense of chaos. Rather, there is an effort to make the army completely subordinate to the political centre at a time when its operational efficiency is becoming a key instrument of state strategy.

It is a delicate operation. This is why a brief statement about "serious violations of discipline and law" is a much bigger story than it first appears.

It indicates that the Party no longer regards the military leadership as a stable given but as a domain that is constantly being reshaped, even at the cost of short-term uncertainty.

This process enters a decisive phase when a new command staff is selected. At that point, it will become clear whether the objective is merely control or the long-term functionality of the system.