The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit opened in Tianjin on 31 August and will last until 1 September.

Announced as the largest meeting to date, it is intended to be a showcase for Chinese diplomacy at a time when Beijing is facing trade tensions with the United States and trying to present an alternative to the Western order.

But the first day of the summit already shows that, behind the grandiose images and numerous delegations, lies an organisation burdened with deep contradictions and limited capacity for joint action.

The most important leaders have arrived in Tianjin: Russian President Vladimir Putin, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian, Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres.

The mere fact that more than twenty heads of state and government are coming together in one place seems impressive.

However, the question remains as to whether real political and security policy cohesion can be expected beyond the protocol.

India and China: an attempt to open a channel

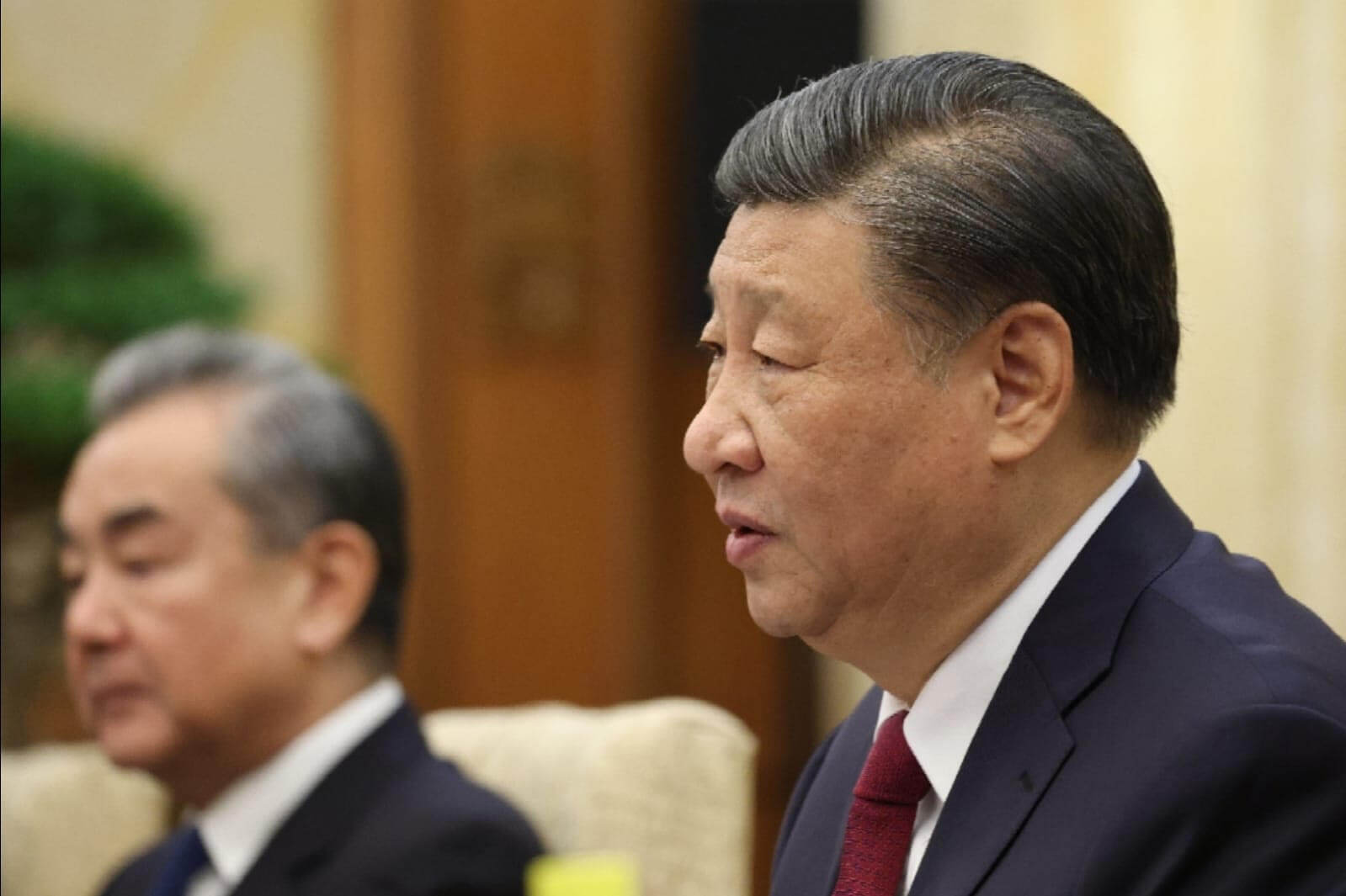

The bilateral meeting between Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi drew the most attention on the first day. It was their first direct dialogue after seven years and thus sent an important signal.

They discussed the border issue, the visa regime, resuming flights, and cultural exchange. Official statements indicate that Modi and Xi reached a consensus to prevent differences from turning into conflicts and to reinforce border management mechanisms.

This does not mean that the problems have been solved. The border between the two countries remains militarised, and their strategic interests diverge.

The meeting in Tianjin is more of a pragmatic damage control exercise than a signal for genuine rapprochement

India is an important partner of the United States in the Indo-Pacific region, is part of the Quad format and is dependent on American technologies and investments. At the same time, it cannot afford to completely freeze relations with China.

The meeting in Tianjin is therefore more of a pragmatic damage control exercise than a signal for genuine rapprochement.

For China, it is of the utmost importance that Modi did not avoid the summit. His presence gives Beijing the argument that the SCO is not just a forum for authoritarian regimes but a platform in which India, a democratic country and an emerging economic power, also participates.

For India, this is an opportunity to show strategic autonomy and to demonstrate that it remains part of Western alliances but does not close the door of communication with China.

Russia on the defensive

Vladimir Putin arrived in Tianjin on the morning of 31 August. His arrival had a strong symbolic dimension: a red carpet, a protocol reception and Chinese state media reporting that relations are the "best in history".

This is the message the Kremlin wants to send to the domestic public at a time when the Russian economy is struggling with a significant decline in trade and the increasingly severe consequences of sanctions.

For Moscow, the summit is an opportunity to show that it is not isolated and that it still has a place in international forums. However, the actual benefits are modest.

Putin uses multilateral forums to mask the reality of Russia's deteriorating position on the global stage

Trade between Russia and China has declined this year, confirming that even the partnership with Beijing has not immunised Moscow against the consequences of the war in Ukraine or the breakdown of relations with the West.

Putin came for photos and words of solidarity, but it is unlikely that he will derive any concrete economic or security benefits from Tianjin.

His position is defensive: he uses multilateral forums to mask the reality of Russia's deteriorating position on the global stage.

An organisation that brings opposites together

Today, the SCO brings together countries that together account for more than 40 per cent of the world's population and around a quarter of global GDP. On paper, this looks impressive. In practice, it is a forum in which there is no real cohesion.

The members have conflicting security interests and different foreign policy orientations. India and China are strategic rivals, India and Pakistan are in perpetual conflict, and Turkey's presence in Tianjin further highlights the contradictions — Ankara is not a member but a partner in the dialogue, yet appears to be an active participant.

This emphasises the fluidity of the framework: the SCO is open to countries that want to show a presence outside Western structures, but their participation does not imply a common strategy or political commitment.

There is a lack of mechanisms that would oblige the members to implement joint decisions

The programme for the summit in Tianjin provides for the adoption of declarations on regional cooperation, security, and trade. A document on the "SCO Vision to 2035" is expected.

However, the experience of previous summits shows that the declarations usually remain at the symbolic level, i.e., only on paper. There is a lack of mechanisms that would oblige the members to implement joint decisions.

For China, the image itself is more important than the content. The ability to bring together leaders from different parts of the world and present itself as the centre of an alternative multilateralism.

For many participants, including Russia, the summit is more an opportunity for protocolar confirmation of political existence than for real initiatives.

Beijing and "customised" multilateralism

The presence of UN Secretary-General António Guterres in Tianjin lends Beijing additional weight. In his opening speech, Xi Jinping spoke of "supporting multilateralism" and the role of the United Nations. However, China's view of multilateralism is selective.

Beijing supports global rules when they suit it and rejects them when they restrict its interests in the South China Sea, in Taiwan or in connection with Western sanctions.

This framework gives China room to present its global ambitions

The SCO is thus becoming an instrument of Chinese foreign policy. Instead of serving as a functional international organisation, China is using the SCO as a platform to project its power and legitimise its own agenda.

This framework does not bring the members any great advantages, but it does give China room to present its global ambitions.

Global implications

The summit in Tianjin is taking place at a time when the world is facing several parallel crises: the trade war between the US and China, the war in Ukraine, tensions in the Middle East and climate change.

The SCO does not offer answers to any of these questions. Rather, it serves as a space in which states can show that they are not completely tied to the West and have an alternative forum for meetings.

China will present the Tianjin declarations as proof of multipolarity, although in practice they are not binding on any member - Xi Jinping

China will present the Tianjin declarations as proof of multipolarity, although in practice they are not binding on any member - Xi Jinping

For India, Tianjin is an opportunity to test the limits of relations with China but also to avoid complete identification with American strategy.

For Russia, the summit is an antidote to isolation, if only a symbolic one. For China, it is a demonstration of power and an attempt to shape the narrative of multipolarity.

In itself, this does not mean that the SCO is without significance. It shows what a world looks like, in which countries are less willing to decide completely in favour of one bloc.

At the same time, however, it also shows the limits: a lack of trust, conflicting interests, and fragmentation make it impossible for this organisation to develop into a serious counterweight to the West.

Tianjin is already revealing the dynamics of the SCO's future.

India will persist in maintaining minimal contacts with China and will not harbour any illusions of a strategic rapprochement, ensuring its continued reliance on the West.

Russia will continue to use the SCO as a stage to demonstrate its political survival, but increasingly without the ability to shape the course of the summit or influence the decisions of the other members.

China will present the Tianjin declarations as proof of multipolarity, although in practice they are not binding on any member.

What will keep the SCO afloat in international politics is its symbolic function. For many countries of the Global South, the mere opportunity to participate in a forum outside Western institutions has value, regardless of the limited results.

But this is where the limit lies — the SCO remains a stage onto which ambitions are projected, not a game-changing platform.

Tianjin 2025 is not a turning point but a reflection of current contradictions. China is using it to assert its own power; Russia to conceal its weakness; and India is using it to preserve its freedom of action.

This combination makes the SCO significant in terms of numbers but modest in terms of content. It is this imbalance between image and content that explains why this forum will remain a secondary, but not insignificant, arena of international relations.