Over the past year, the United States and China have consolidated their positions as the world’s leading superpowers, largely at the expense of everyone else.

In both countries, growth has remained strong despite the disruptions and volatility caused by the breakdown of the rules-based international order, which US President Donald Trump and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping have actively fueled.

Yet these headline figures conceal deeper weaknesses. In the US, strong growth masks a K-shaped recovery that has given rise to a politically toxic affordability crisis.

Trump’s tariffs, in particular, have kept inflation above the Federal Reserve’s target while failing to deliver any meaningful reduction in the current-account deficit.

In China, by contrast, robust growth has been driven primarily by surging exports, with the country’s trade surplus surpassing $1 trillion for the first time in 2025.

But the success of Xi’s “new quality productive forces” agenda has been offset by falling home prices, high youth unemployment, and sluggish wage growth, all of which have dampened consumption.

As a result, the long-promised rebalancing of China’s growth model has once again been postponed.

A race for technological supremacy

While their motivations and policy tools differ, both the US and China are engaged in a race for technological supremacy driven by massive investment.

For the US, technological leadership is key to maintaining economic and financial dominance; for China, it locks in foreign dependence on Chinese production and supply chains.

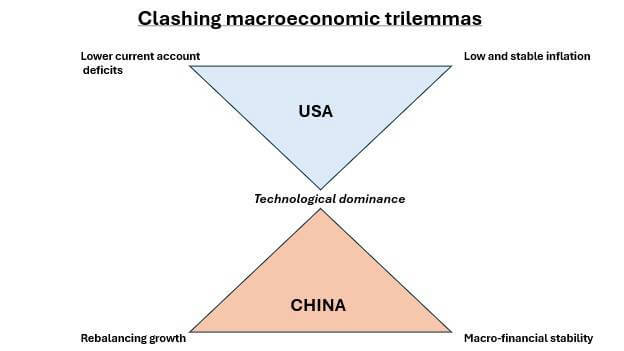

But each is constrained by macroeconomic trilemmas. Beyond technological dominance, the US is also seeking to reduce its current-account deficit and maintain low and stable inflation.

The latter two objectives are incompatible with the current investment race.

If the US wants to achieve technological dominance and low inflation, tariffs would have to be rolled back, and monetary policy would need to be tightened

Sustaining leadership in frontier industries requires continuous deregulation and inflows of foreign capital, which imply continuous external deficits.

Reducing the trade deficit would require higher domestic savings and a weaker dollar, putting pressure on the Fed to cut interest rates aggressively. The inevitable result would be higher inflation.

To be sure, a combination of higher tariffs, meddling with the Fed, a weaker dollar, and pressure on foreign governments to dismantle regulatory and non-regulatory barriers to US exports could help reduce the external deficit while supporting investment.

But this policy package would entrench high inflation and exacerbate the affordability crisis.

If the US wants to achieve technological dominance and low inflation, tariffs would have to be rolled back, and monetary policy would need to be tightened.

The resulting capital inflows would drive up the dollar, widening the current-account deficit.

China faces a different trilemma

China faces a different, but equally stark, trilemma. Alongside technological dominance, its other objectives are maintaining macro-financial stability and sustaining wage and consumption growth.

To pursue its “new quality productive forces” agenda while remaining the world’s leading manufacturing hub, it must subsidize investment in emerging sectors without abandoning traditional industries.

But this strategy will lead to overinvestment, excess capacity, falling profitability, and deflationary pressures, as well as large trade surpluses.

And with the real-estate sector still in crisis, the risk of spillovers into the financial system is uncomfortably high.

Therefore, preserving macro-financial stability requires heavy regulatory and fiscal intervention.

The pursuit of high investment and financial stability will necessarily come at the expense of economic rebalancing

But the pursuit of high investment and financial stability will necessarily come at the expense of economic rebalancing.

Consumption growth remains weak, deflation risks are becoming entrenched, and efforts to offload overcapacity through exports are bound to fuel trade protectionism abroad.

An alternative path, outlined in the conclusions of October’s Fourth Plenum of the Communist Party of China, would combine large investments in new productive forces with a decisive push to boost domestic consumption.

This could be achieved through more expansionary fiscal and monetary policies and strengthening the social safety net.

Such an approach would help alleviate deflationary pressures, but would also increase China’s already high debt levels, thereby raising the risk of a future financial crisis.

A different global equilibrium

Sooner or later, the US and China will have to confront the growing tension between their pursuit of technological dominance and their domestic macroeconomic goals.

Seeking absolute rather than comparative advantage could lead to the misallocation of domestic resources and contribute to a global investment glut, especially as the European Union and India are pursuing similar strategies, albeit more cautiously.

That tension is unlikely to remain contained. A collapse of the AI bubble and the inability to bring either inflation or the current-account deficit under control in the US, along with the materialization of macro-financial risks in China, would have major repercussions on the international economy.

A different global equilibrium is economically feasible but would be politically difficult to sustain.

As the chart below shows, reconciling their conflicting objectives would require the US and China to slow an investment race that increasingly resembles an arms race.

Such a shift would also require the two superpowers to abandon their predatory tactics and revive some form of multilateral cooperation.

That change is unlikely to be voluntary, but the mounting economic costs and internal strains generated by excess investment may – hopefully – deliver it.

Moreno Bertoldi is Senior Associate Research Fellow at the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI).

Marco Buti is Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa Chair at the European University Institute’s Robert Schuman Center and an external fellow at Bruegel.