Europe is attempting to end the long-standing asymmetry in its relations with Chinese investors.

Following the informal meeting of trade ministers in Copenhagen, the question remains open: should the entry of Chinese capital into the EU be linked to the genuine transfer of technology, know-how, and intellectual property to Europe? The aim is not a procedural formality but a significant shift.

Danish Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen stated that if the EU invites Chinese investments, they should be subject to the precondition of technology transfer.

Maroš Šefčovič, Executive Vice President for the European Green Deal and Vice President for Interinstitutional Relations at the European Commission, emphasised that only investments bringing real value to Europe are welcome—new jobs, development centres, and intellectual property registered within the European legal system.

The European Commission has been tasked with translating these political positions into concrete proposals and operational rules to apply to all future Chinese projects in the Union by the end of the year.

Resources as political pressure

At the beginning of October, China tightened export controls on rare minerals—key raw materials for the production of batteries, magnetic systems, microchips, and modern military technology.

This move was seen in Brussels as a warning: the Chinese side is prepared to use resources as a means of political pressure.

That is why European officials increasingly emphasise that Chinese investments in the EU must provide measurable technological value for Europe. Investments can no longer be limited to capital and assembly plants; part of the knowledge, research, and intellectual property is expected to remain within the Union. Otherwise, Europe risks financing its own dependency.

This move by the EU should not be seen as an isolated initiative but as part of a broader, coordinated policy among Western partners.

The finance ministers of the G7 countries agreed that it is necessary to respond jointly to Chinese export controls

On the sidelines of meetings in Washington, the finance ministers of the G7 countries agreed that it is necessary to respond jointly to Chinese export controls and to accelerate the diversification of sources of supply for key minerals.

The message was clear: the issue of China's resources is no longer a matter of trade balance but a strategic issue of industrial and security policy.

In this context, the European demand that Chinese investments be conditional on technology transfer is not a dispute between trading partners but part of the defence of long-term technological independence.

Real investments and real technology

In practice, real technology transfer under European conditions would require concrete, verifiable obligations from Chinese investors.

A company entering the EU market would have to open a research centre in one of the member states, with a budget and number of experts corresponding to the scope of the project.

Maroš Šefčovič emphasised the need for "real investments" and "real technology"

Maroš Šefčovič emphasised the need for "real investments" and "real technology"

The intellectual property arising from that process must be registered and protected within the European legal system and not transferred abroad without control.

European partners expect local engineers and technicians to be trained in development processes, not only in routine manufacturing and assembly, and that EU suppliers have access to data and interfaces enabling their inclusion in technology value chains.

This is the essence of the concept presented by European officials. Maroš Šefčovič emphasised the need for "real investments" and "real technology", while Lars Løkke Rasmussen specified that this is a prerequisite for any future cooperation.

This approach does not replicate the Chinese model of mandatory joint ventures but introduces a clear principle: investment in Europe must make a demonstrable contribution to the European technological and industrial base.

Reducing legal risk and maintaining credibility

The most sensitive aspect of the entire initiative will be its legal framework.

The European Union must establish a new practice within the existing rules of the World Trade Organization, as well as in its own regulations on state aid, free movement of capital, and mechanisms for screening foreign investments at the member state level.

Therefore, it is almost certain that the European Commission will initially adopt a more lenient, adaptive approach.

Rather than introducing a single mandatory regime, the Commission will most likely set shared guidelines and sectoral criteria to be gradually incorporated into national investment approval procedures.

Each state will retain formal jurisdiction but with increased supervision and regular verification of compliance throughout the duration of the projects

Each state will retain formal jurisdiction but with increased supervision and regular verification of compliance throughout the duration of the projects.

Only when such a system proves viable in several strategic areas will it be possible to introduce stronger and uniform rules at the Union level.

That approach has a clear logic. Legally, it reduces the risk that the courts will strike down the new rules as disproportionate or discriminatory.

Economically, it alleviates investors’ fears and prevents the sudden departure of capital.

Politically, it allows member states to remain part of a shared framework without giving up their own interests and control models.

This lays the foundation for a European regime that combines market protection and legal sustainability, without sacrificing credibility in international trade relations.

Europe’s balancing act

The economic aspect of this decision is complex. In recent years, a greater number of member states have become directly dependent on Chinese investments, primarily in the production of electric vehicles, batteries, renewable energy sources, port infrastructure, and logistics.

If the new rules are set too strictly, some capital may be withdrawn or redirected to third countries, which would slow planned projects and jeopardise the goals of the green transition.

However, giving in carries an even greater risk. Europe would continue to finance the energy transformation with public money, while technological gains, patents, and research would remain outside its borders.

In this gap, there are increasingly loud proposals to introduce a “trial regime” in sectors where performance can be measured most quickly—primarily in the production of batteries, recycling, components for wind and solar power plants, and energy electronics.

Within a year or two, results can be seen precisely: how much research is carried out in the EU, how many patents are created, and what share of European value is in exports

There, within a year or two, results can be seen precisely: how much research is carried out in the EU, how many patents are created, and what share of European value is in exports.

Such an approach provides Brussels the opportunity to assess the effectiveness of the new policy without causing sudden disruptions.

It aligns logically with the political messages from the meeting in Copenhagen and reflects the pressure in Europe resulting from Chinese controls on rare minerals.

The idea is clear: to retain capital but require it to generate knowledge within Europe.

A Western attempt to curb Chinese influence

The new European rules will inevitably have foreign policy implications. Beijing will perceive them as a Western attempt to curb Chinese influence in key industries under the new conditions.

The response could be subtle but effective—administrative delays in permits for European firms, regulatory obstacles, or targeted countermeasures in sectors important to individual EU member states.

For this reason, Brussels is already paying close attention to the tone of future regulations.

The language must be clear enough to prevent circumvention of the rules but also flexible enough to allow sector-by-sector negotiations and avoid open trade conflict.

A unified system of control

In the coming months, Brussels will seek to establish a clear and measurable framework for the new policy.

The first step will be to create a system to verify the real benefit of each foreign investment.

In the battery and electric vehicle supply chains, where investigations into subsidies and market distortions are already underway, investment and trade instruments will naturally converge - CATL, Germany

In the battery and electric vehicle supply chains, where investigations into subsidies and market distortions are already underway, investment and trade instruments will naturally converge - CATL, Germany

Member states will receive a model that can be easily applied when approving projects—a checklist indicating whether the investment brings knowledge, employs professional staff, and transfers technology within the EU.

The next step is to agree on shared indicators that cannot be bypassed. The number of researchers and engineers employed in the EU, the percentage of the budget allocated to research and development within the Union, and ownership of patents and software registered to European entities, as well as reports on the training of local teams and obligations to European suppliers—all these will become mandatory components of the assessment of each investment.

The third element will be to link this policy with existing EU trade measures.

In the battery and electric vehicle supply chains, where investigations into subsidies and market distortions are already underway, investment and trade instruments will naturally converge.

In this way, the EU aims to build a unified system of control—from factory to export—in which the criteria will be the same for all.

A framework for real value

The message to Chinese companies that want a long-term presence in Europe is now quite clear.

Those that quickly open research centres in member states, register part of their patents and software solutions in European entities and include local universities and institutes in joint projects will get a more stable position and more predictable approval of new investments.

Investments that bring knowledge and employ European experts have a future, and those that leave no trace do not

Such a presence shows that the investment has a real value for the European economy, not just a commercial interest. Companies that ignore this will face lengthy procedures, additional checks, and uncertainty in every new project.

In areas that are already the subject of investigations - electric vehicles, batteries, solar and wind energy - this approach can also serve as a way out of possible trade conflicts.

Demonstrable local value and a visible contribution to the European technological base could ease the pressure to introduce new tariffs and restrictions, giving Chinese companies a clearer framework: investments that bring knowledge and employ European experts have a future, and those that leave no trace do not.

Europe’s key challenge

For European governments, the key challenge will be to achieve a balance.

Too much leniency would turn the new rules into an empty form, while too much strictness could stop the flow of capital and slow down projects already underway.

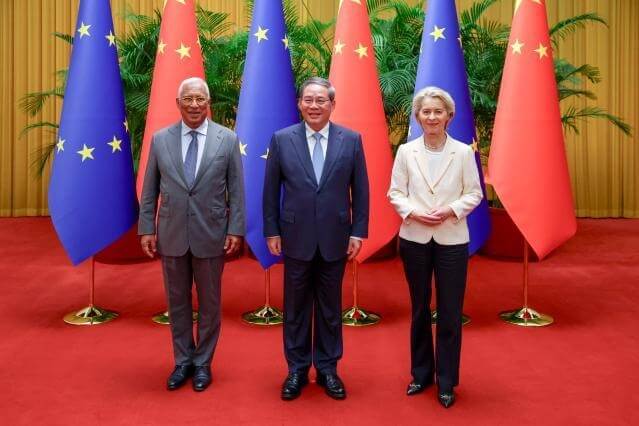

A reasonable move by Beijing would be to accept the basic conditions and shape their implementation through practice - Antnio Costa, Li Qiang, Ursula von der Leyen

A reasonable move by Beijing would be to accept the basic conditions and shape their implementation through practice - Antnio Costa, Li Qiang, Ursula von der Leyen

That is why political skill will be crucial - it is necessary to establish a shared minimum of rules that are strong enough to be applied in practice and reasonable enough to be accepted by the market.

With this move, the European Union is laying the foundations of a new industrial policy.

If it consistently implements the "technology for the market" principle, it can rebuild parts of its industrial base and reduce its dependence on technologies emerging outside its borders.

This would restore Europe's negotiating power in areas where it has been only a consumer of other people's knowledge for years.

The loss of some capital and a slower pace of investment will be the inevitable price, but it is better than a scenario in which Europe finances the development happening elsewhere.

The relationship with China remains a key unknown. A reasonable move by Beijing would be to accept the basic conditions and shape their implementation through practice.

Any attempt at pressure, whether through restrictions on raw material exports or veiled barriers to European firms, would only hasten the EU's decision to move or double down on critical supply chains beyond China's reach.

The messages coming from Copenhagen and Washington already confirm such a course - a joint approach of partners, expanding sources of supply and insisting that foreign capital leaves a real technological footprint in Europe, not just a balance of investments.

Europe remains open to cooperation but no longer agrees to unequal terms. Its marketplace remains available but is no longer free. Any investment must bring knowledge, technology and real value, not just factories and capital.