I recently watched the first season of Netflix’s series “The Recruit”. To be accurate: I managed only the first episode. As a career CIA officer, the disconnect between my experience running espionage operations and the Hollywood portrayal was just too absurd to stomach. “Gray Man,” “Jack Ryan,” and “The Agency” were also particularly painful in this regard.

The screen version of the intelligence world displays perplexing interest in getting a few small details right while otherwise throwing common sense to the wind.

Why hire some ex-intelligence officer to assure that Jack Ryan’s badge looks real and the file folders are the right color if the basic story has no connection with reality whatsoever?

The handful of people who know what a real burn bag for classified papers looks like will also be the most critical of the show’s other failings. When a new series like “The Recruit” drops, I can count on numerous texts from my former colleagues commenting on its foolishness.

Hollywood’s failure

Of course, Hollywood’s primary interest is to entertain the audience. Car chases, explosions, escapes across rooftops, and murders – lots of murders – do provide a sugar high, but they fail as more enduring stories.

Placing the espionage genre inside the category of “action films” has been a disservice to quality writers who know how to tell a real story, and ultimately a disservice to the audience.

The underpinnings of the spy game are exactly the thing Hollywood does best: human relationships

It is possible, indeed realistic, to explore in high-stakes issues with life and death consequences without having a lone intelligence officer chase someone or shoot them. Having spent a career inside the intelligence community, I can state that realistic spy drama makes for more compelling story-telling.

Hollywood’s failure to examine the real world of espionage is more surprising because the underpinnings of the spy game are exactly the thing Hollywood (and literature) does best: human relationships.

The relationship between a source and his/her handler

Real espionage is about the human factor. It explores flawed individuals, trust, betrayal, ego, manipulation, secrecy, psychology, cowardice, bravery and vulnerability, all placed within the pressure cooker of international politics and national security.

It is less a story of good vs. evil than a constant balance of moral and ethical dilemmas in an environment with no obvious answers. Each situation is different and worthy of exploration.

Anyone who has lived in the clandestine world knows that the relationship between a source and his/her handler is often the most intense non-romantic connection that two people can share.

A source betraying his country cannot share his opinions and feelings with anyone else in his life. Living with the knowledge that you could be arrested and killed at any moment provides an atmosphere of intensity when sharing time with the one person who knows your reality.

Hollywood writers should salivate at the opportunity to explore what leads someone to consider risking everything for a venture with no public payoff

The Soviet spy Adolf Tolkachev was so committed to damaging the communist state that he insisted on stealing and passing secret documents to his CIA handler even as he feared he was coming under scrutiny.

Every time he was called to his boss’ office, he would place a CIA-issued suicide pill into his mouth, between his cheek and gums, for fear that it might be a KGB ambush to have him arrested.

He wanted to be able to bite down at any minute so that he wouldn’t give the KGB the satisfaction of interrogating and torturing him. Following the meeting, he would hide the pill and continue spying.

Imagine the intensity of the covert relationship with his CIA handler. Hollywood writers should salivate at the opportunity to explore what leads someone to consider risking everything for a venture with no public payoff.

The real heroes are our sources

A former colleague tells the story of a burgeoning relationship with a senior official of a country with a state-mandated religion. After building trust, the official shared something that he could not tell anyone, not even his wife.

He didn’t believe in God. Unable to discuss his doubts with his friends, he continued to pray with his family, friends and co-workers, always wondering if they too had doubts. Confiding in the wrong person could mean a loss of his job and family.

We all know that the real heroes are our sources that risk their lives to help a country not their own

The one place he could be himself was in his relationship with the CIA. The failure to depict the asset’s perspective is a common lapse in the Hollywood approach. Those of us who spend our careers overseas are sometimes casually labeled as heroes.

We all know, however, that the real heroes are our sources that risk their lives to help a country not their own.

How close is ‘Homeland’ to reality?

By far, the most asked question to anyone with experience in the intelligence community is, “How close is ‘Homeland’ to reality?”

After explaining that real intelligence work doesn’t involve shootouts on American streets or dependence on officers with a grab-bag of personal and professional problems, it is nonetheless difficult to offer an alternative that is closer to reality.

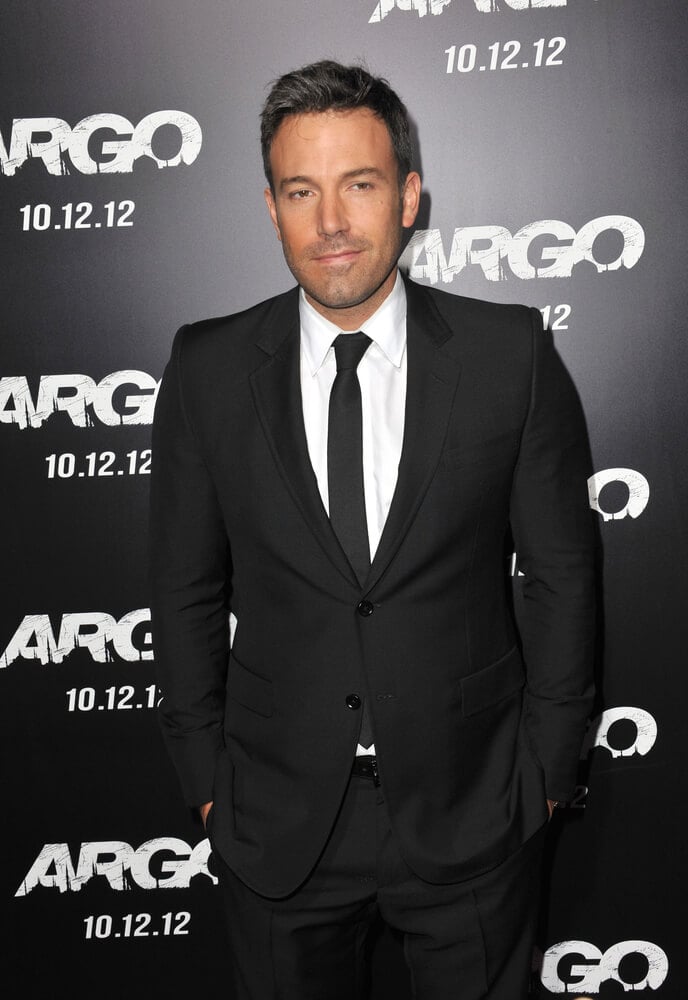

“Argo” gives a good sense of the slow planning and rehearsal that precede a successful operation - Ben Affleck

“Argo” gives a good sense of the slow planning and rehearsal that precede a successful operation - Ben Affleck

Some shows get parts correct (Recent "Intelligence Matters" Podcasts on spy shows). “The Americans” included elements of street tradecraft and a reliance on sources that did not stray too far from reality. “The Spy” with Sacha Baron Cohen provided a look at how intelligence agencies and policymakers can pressure operatives to produce results.

“Slow Horses” captures some of the cynical banter between field officers, and “The Little Drummer Girl” and “Argo” give a good sense of the slow planning and rehearsal that precede a successful operation. While not perfect, the British seem better at infusing reality with entertainment in the espionage realm.

While there are too many to list, there are common tropes in the espionage genre that drive practitioners crazy. Too many shows hew to one fantastic extreme or the other: either there is a single officer with almost superhuman powers (often a “rogue” operative) who, unbound by regulation or law, fights and defeats the system and saves the day, or alternatively the President or CIA Director are choreographing complex operations from thousands of miles away.

Professionals do not sleep with sources

Real intelligence is a team sport that requires bureaucrats to manage budgets, provide political input and oversight, professionals to coordinate resources and provide operational and legal advice, and field operatives who know their environment such that they can execute secure and effective operations in shifting and chaotic circumstances.

In the foreign field, professionals do not engage in blackmail (it backfires), sleep with sources (career ender), try to speed away and lose surveillance (it simply invites more), call sources (or headquarters) on the phone, or shoot their way out of trouble.

Most productions fall into the trap of providing constant motion and action - John Sipher

Most productions fall into the trap of providing constant motion and action - John Sipher

While tracking technology, data analysis and encryption are crucial part of the business, more often it is a single individual who develops a discreet and trusting relationship with a source that provides the piece of information that helps inform policy. It is a people business.

That said, most productions nonetheless fall into the trap of providing constant motion and action. Of course, intelligence agencies accrue some benefit in allowing the myth to remain.

A smaller intelligence service like the British SIS benefits from the reputation of James Bond. Many a potential source may have been swayed to speak to British diplomats and spies, having been brought up with the fantasy that the British maintain some special skill in the art of espionage. Likewise, foes of the Israelis probably hesitate to take action in fear of being assassinated.

Intelligence officers like to see ourselves as the fit, attractive and multi-talented actors on the screen, but the actual skills required to succeed are more mundane – but also rarer.

A good officer must be comfortable dealing with ambiguity. They must have a honed sense of judgment, be able to develop deep relationships and engender trust, be a good listener, have a facility with foreign languages, have a sense of spatial awareness and ability to operate on the street, write effectively, be comfortable in foreign cultures and keep up-to-date on political, diplomatic, scientific and military issues.

Sometimes we need to carry a gun or trek to places our military colleagues cannot go, but shooting our way out of trouble or using our sexual wile to infiltrate a closed facility are not taught at our training facilities – and we watch them on -screen with amusement and bafflement.

John Sipher ( @johnsipher.bsky.social ) is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and co-founder of Spycraft Entertainment. He worked for the CIA’s Clandestine Service for 28 years and is the recipient of the Agency’s Distinguished Career Intelligence medal. He is also a host and producer of the "Mission Implausible" podcast, exploring conspiracy theories.