This summer, US President Donald Trump dropped a tariff hammer on nearly 100 countries, jolting markets, provoking protests in allied capitals, and sending trade lawyers scrambling.

While the White House says it is using tariff leverage to fix trade deficits (among other rationales), the numbers tell a different story.

If the tariffs truly were aimed at cutting trade deficits, the logic would be straightforward.

The highest rates would be imposed on countries where the value of US imports most exceeds the value of US exports, relative to the size of the US economy.

By that measure, the biggest bilateral merchandise-trade gaps, excluding China, are with the European Union (-0.85% of US GDP), Mexico (-0.62%), Vietnam (-0.45%), and Japan (-0.25%).

Under a deficit-driven policy, these economies would be at the top of the chart.

Instead, the EU is facing a tariff of just 15%, Mexico 25%, Vietnam 20%, and Japan 15%.

Meanwhile, countries where the US runs a surplus or only a modest deficit have been hit with some of the steepest tariff rates. Imports from Brazil, with which the US has a small +0.03% surplus, face a 50% rate – the highest of any country. The rate for Laos, with which the bilateral deficit is just -0.003% of US GDP, is 40%.

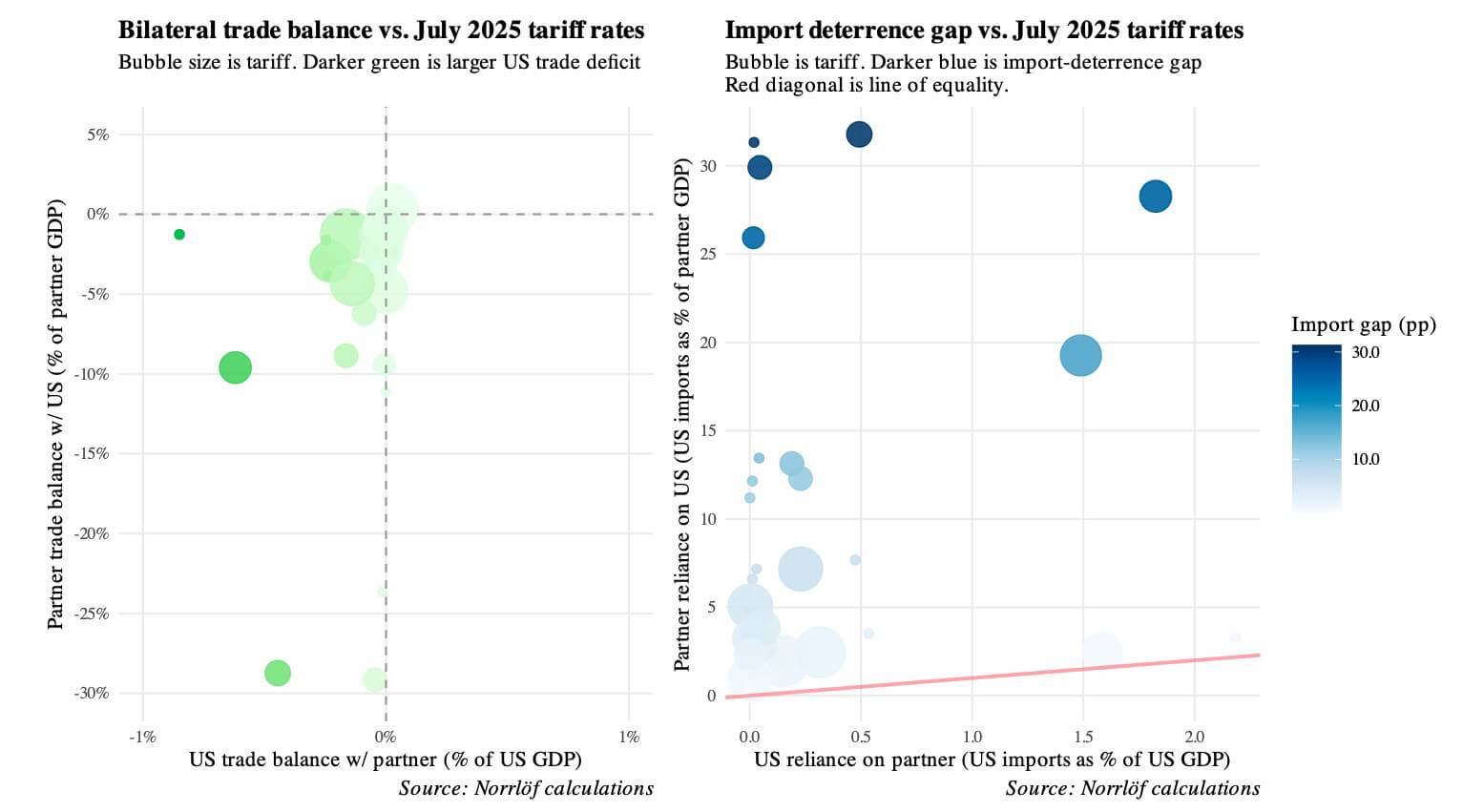

In the figure above, the darkest green bubbles are the countries with which the US runs its largest trade deficits.

If tariffs were really about closing these deficits, the bottom left corner (with the darkest shades) would be packed with the largest bubbles, indicating steep penalties on the biggest offenders.

Instead, it’s almost empty, with just one small bubble and a few mid-size ones.

The largest bubbles are pale, clustered around the zero line and even spilling into surplus territory. These data confirm that the US is imposing its highest tariffs on countries where it barely runs a deficit, or even has a trade surplus.

Who most relies on the US market?

If the tariffs were about leverage, the logic would be different. Here the question isn’t whom the US owes most, but rather who most relies on the US market.

A country that sells a large share of its GDP to the US and buys very little from America in relative terms, is in a weak bargaining position.

By this measure, those with the widest dependence gaps (high above the diagonal line in the right-hand graph) would be charged the highest rates.

That would put Vietnam (which generates 32% of its GDP from exports to the US), Guyana (31%), Cambodia (30%), Mexico (28%), and Nicaragua (26%) squarely in the crosshairs.

Yet, except for Mexico, which faces a 25% tariff, these countries all face rates of 20% or less.

The top rates have been assigned to less dependent countries: Brazil (2% of GDP from US sales) and India (2.5%)

Instead, the top rates have been assigned to less dependent countries: Brazil (2% of GDP from US sales) and India (2.5%).

In this figure, the biggest bubbles should sit in the upper left above the diagonal, where partners are heavily reliant on US buyers and the US has low dependence.

Instead, this zone has small and mid-size bubbles, while the largest bubbles hover further down, with some drifting right.

Trump is rewarding alignment

Neither deficits nor leverage explain these figures. Instead, they make more sense when viewed through the lens of politics.

The Trump White House is rewarding alignment, punishing independence, and targeting sectors linked to strategic rivals.

Consider Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is a negligible US deficit partner with minimal dependence on the US, but its courting of Chinese infrastructure investment (including hydropower projects and highways under China’s Belt and Road Initiative) positions it as politically misaligned.

Similarly, Myanmar, which faces a 40% tariff, is a negligible US deficit partner with very low US reliance, yet it remains deeply dependent on Chinese military and economic support, and has strengthened defense ties with Russia since the 2021 coup.

Serbia, facing a 35% tariff, has a small US deficit and similarly low leverage, but stands out for its strategic energy and security alignment with Russia (it relies on Russian gas and has repeatedly received US sanctions waivers for its Russian-linked oil company).

The EU avoided a steeper hike after agreeing to cooperate on export controls and data-sharing

Brazil is one of the few targeted partners where the US runs a small trade surplus; but as a key supplier of iron ore, it enjoys rising strategic mining clout amid shifting global supply chains, and it has refused to bend to Trump’s political demands.

Others have been far more pliant. The EU avoided a steeper hike after agreeing to cooperate on export controls and data-sharing.

Australia secured the base 10% rate after deepening its defense ties with the US. Japan’s rate rose but stayed below the maximum after it aligned semiconductor policy with US objectives.

US market access has become a political privilege

Using tariff rates to reward compliance with US goals and penalize autonomy is a sharp break from the rules-based system that prevailed under the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs and the GATT’s successor, the World Trade Organization.

While Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama also linked trade to security aims, they did so through formal agreements and multilateral deals that preserved goodwil

While Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama also linked trade to security aims, they did so through formal agreements and multilateral deals that preserved goodwil

While US Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama also linked trade to security aims, they did so through formal agreements and multilateral deals that preserved goodwill.

Trump’s approach is blunt, rapid, and highly public – from the “Liberation Day” announcement of reciprocal tariffs (invoking emergency powers) on April 2, to the July 31 rewrite, the August copper-tariff hike, and the decision to eliminate the $800 duty-free threshold.

US market access has become a political privilege that is conditional, revocable, and used to police alignment.

This approach may yield short-term wins. But it risks weakening the alliances and institutions that have magnified US economic power for decades.

The tariff schedule is no economic blueprint. It is a scorecard, and a ledger of this administration’s strategic priorities.

Carla Norrlöf is Professor of Political Science at the University of Toronto.