As African leaders gather in Cape Town for the African Water Investment Summit, there can be no equivocation: the world faces an unprecedented water crisis that demands a paradigm shift in how we value and govern our most precious resource.

The scale of the challenge is staggering. Over half the world’s food production now comes from areas experiencing declining freshwater supplies.

Two-thirds of the global population faces water scarcity at least one month per year. More than 1,000 children under five die every day, on average, from water-related diseases.

And if current trends continue, high-income countries could see their GDP shrink by 8% by 2050, while lower-income countries (many in Africa) face losses of 10-15%.

Yet this crisis also presents an extraordinary opportunity. As South Africa assumes the G20 presidency (for which I have been appointed special adviser to President Cyril Ramaphosa), it can champion a new economics of water that treats the hydrological cycle as a global common good, rather than as the source of a commodity to be hoarded or traded.

The economic case for action is compelling. The International High-Level Panel on Water Investments for Africa shows that every $1 invested in climate-resilient water and sanitation delivers a return of $7.

With Africa requiring an additional $30 billion annually to meet the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) on water security and sustainable sanitation, the financing gap is significant; but it is surmountable with the right strategy.

The Global Commission on the Economics of Water (which I co-chaired with Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the director-general of the World Trade Organization, Johan Rockström, the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, and Singaporian President Tharman Shanmugaratnam) recently called for such a strategy.

Water connects us all

Treating water as a global common good and adopting mission-oriented approaches to transform the crisis into an opportunity requires that we recognize three critical facts.

First, water connects us all – not just through visible rivers and lakes, but through atmospheric moisture flows that travel across continents.

Second, the water crisis is inseparable from climate change and biodiversity loss, each of which accelerates the others in a vicious cycle.

There is a tendency to derisk private capital without ensuring public returns

And, third, water runs through every SDG, from food security and health to economic growth.

Yet too often, water investments follow the failed playbook of climate and development finance.

There is a tendency to derisk private capital without ensuring public returns; to fund projects without strategic direction; and to treat water as a technical problem, rather than a systemic challenge.

Such approaches risk creating water infrastructure that serves investors more than communities, exacerbates existing inequalities, and fails to address the interconnected nature of the water, climate, and biodiversity crises.

Mission-oriented investments

This interconnectedness demands a new economic framework that aims to shape markets proactively rather than simply fixing failures after the fact.

We need to move from short-term cost-benefit thinking to long-term value creation, and that calls for mission-oriented investments that shape markets for the common good.

Missions require clear goals – like ensuring that no child dies from unsafe water by 2030.

Once goals are established, all financing can be aligned with them through cross-sectoral approaches spanning agriculture, energy, manufacturing, and digital infrastructure.

Rather than picking sectors or technologies, the point is to find willing partners across all industries to tackle shared challenges.

Such mission-oriented investments can also lead to economic diversification, creating new export opportunities and development pathways.

More than $700 billion per year is channeled into water and agriculture subsidies that often incentivize overuse and pollution

Consider Bolivia’s approach to lithium extraction. Rather than simply exporting raw materials, the country is developing strategies to avoid the traditional “resource curse” by building domestic battery-production capabilities and participating directly in the energy transition.

In doing so, it is converting its resource wealth into innovation capacity, strengthening value chains, and creating new export markets for higher-value activities.

As matters stand, more than $700 billion per year is channeled into water and agriculture subsidies that often incentivize overuse and pollution.

By redirecting these resources toward water-efficient agriculture and ecosystem restoration, with clear conditions attached, we could transform the economics of water overnight.

To that end, public development banks can provide patient capital for water infrastructure, while requiring private partners to reinvest profits in watershed protection.

Water security

Africa is uniquely positioned to lead this transformation. Its vast supply of groundwater remains largely untapped, with 255 million urban inhabitants living above known supplies.

Combined with affordable solar power, these supplies present an opportunity to revolutionize agriculture.

By focusing on efficiency and reuse, as well as on capacity building, data-sharing, and monitoring and evaluation, this relatively stable groundwater resource, accessed by solar-powered pumps, can be a decentralized alternative minimizing the emissions, waste, and other environmental costs implied by larger infrastructure projects that disrupt natural waterflows.

Through Just Water Partnerships – collaborative frameworks that pool such solar-groundwater projects for increased bankability while ensuring community ownership – international finance can be channeled toward water infrastructure that serves both national development goals and the global common good.

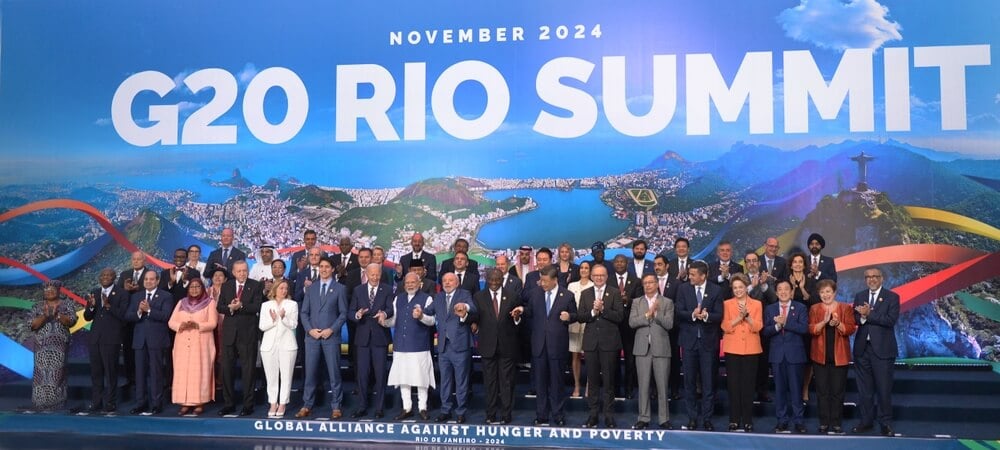

Just as Brazil has used its G20 leadership to drive climate action, South Africa can make water security central to the global economic agenda

Just as Brazil has used its G20 leadership to drive climate action, South Africa can make water security central to the global economic agenda

South Africa’s G20 presidency – the first ever for an African country – offers a historic platform to advance this agenda globally.

Just as Brazil has used its G20 leadership and role as host of the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) to drive climate action, South Africa can make water security central to the global economic agenda.

With the 2026 UN Water Conference on the horizon, and with the international community recognizing that climate change cannot be tackled without also addressing the water crisis, the time is right for bold leadership.

The African Water Investment Summit is not just another gathering, but should be a watershed.

This is the moment when we should shift from treating water as a local resource to governing it as a global common good, moving from crisis management to proactive market shaping and from viewing mission-oriented investment as a cost to recognizing it as the foundation of sustainable growth.

Water security underpins Africa’s aspirations for health, climate resilience, prosperity, and peace. With young Africans set to constitute 42% of global youth by 2030, investing in water is tantamount to investing in the world’s future. The question isn’t whether we can afford to act, but whether we can afford not to.

Mariana Mazzucato, Professor in the Economics of Innovation and Public Value at University College London, is Founding Director of the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Co-Chair of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water, and Co-Chair of the Group of Experts to the G20 Taskforce for a Global Mobilization Against Climate Change. She was Chair of the World Health Organization’s Council on the Economics of Health For All.