One of the unintended consequences of climate financing – meant to help the transition to green fuels and respond to extreme weather – is the rising debt burden of developing countries as they pay back $7 for every $5 they get in loans from rich countries.

Most of the “profiteering” by rich countries comes from the standard rates of interest that they charge, and France, Japan and Italy are among the worst culprits, according to research by Oxfam and the CARE Climate Justice Centre.

Their report came out before the International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction on 13 October that started in 1989 following a call by the UN General Assembly to raise awareness of climate change’s dangers.

More and more people are experiencing heat waves, drought, flooding, displacement and death. But there appears a lack of urgency in the rich world over what is needed globally to cope.

The richer world that caused much of the pollution causing the present crisis appears unwilling to pay even to avert blowback in the form of rising flows of migration and the dangerous spread of disease.

Profiting from the climate crisis

“Rich countries are treating the climate crisis as a business opportunity, not a moral obligation,” said Oxfam’s Climate Policy Lead, Nafkote Dabi. “They are lending money to the very people they have historically harmed, trapping vulnerable nations in a cycle of debt.”

High-polluting countries have only met 4% of the climate finance needs for eight highly vulnerable African countries — Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Uganda, the report says.

The cost of economic losses linked to natural hazard events averages $202 billion annually

But the meagre amounts of climate finance that have been made available compared to the needs are adding more each year to the debt of developing countries that now stands at $3.3 trillion.

In 2022, developing countries received $62 billion in climate loans, and the report estimates these loans will lead to repayments of up to $88 billion, resulting in a 42% “profit” for creditors.

The cost of economic losses linked to natural hazard events averages $202 billion annually, but the UN’s Global Assessment Report 2025 suggests the real debt figure could be closer to $2.3 trillion.

The true value of climate finance

The UN and others are urging increased funding for disaster risk reduction, particularly through international assistance and public budgets – a tough ask in the age of Trumpian and populist nationalism.

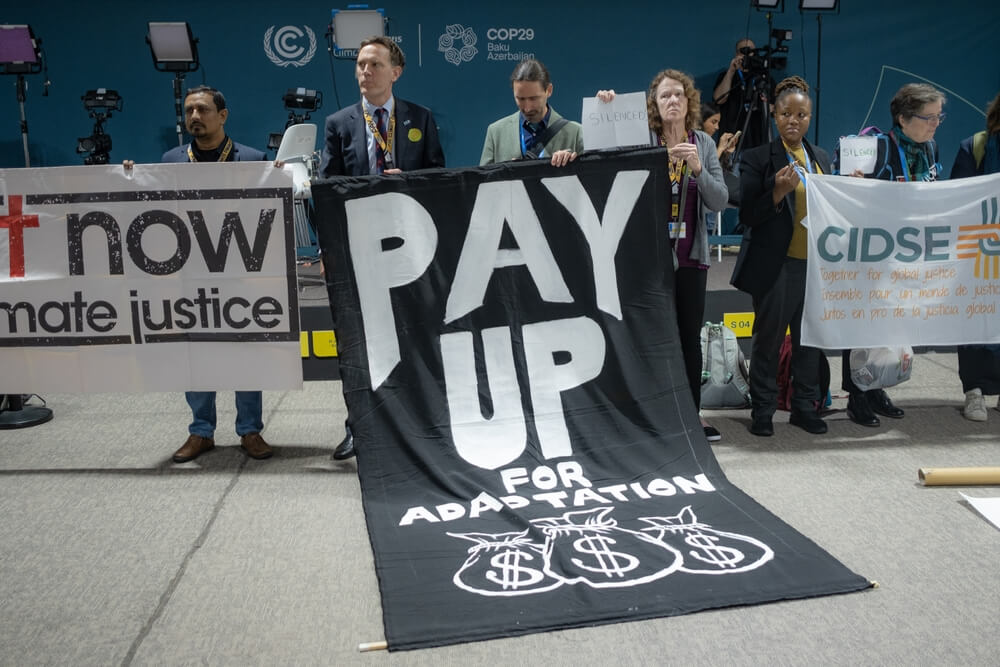

Under an accord reached at the 2015 UN climate COP talks, richer countries agreed to pay vulnerable countries for adaptation to droughts, floods, rising seas and extreme heat, to pay for damage caused by extreme weather, and to transition towards clean energy.

“Every dollar invested in resilient infrastructure in developing countries saves $4 when disasters strike” - Antonio Guterres

Although rich countries claim to have mobilised $116 billion in climate finance in 2022, the true value is only around $28-$35 billion, or less than a third of the pledged amount. Furthermore, donor countries are expected to make “vicious” foreign aid cuts of around 17% this year, says the report.

“Every dollar invested in resilient infrastructure in developing countries saves $4 when disasters strike,” says Antonio Guterres, UN secretary-general. “Governments and donors must scale-up investments in disaster risk reduction.”

COP30 in Belem

Developing countries are pushing for a better deal at the COP30 climate meeting in Belem, in the Brazilian Amazon, next month after being disappointed by the target of $300 billion a year by 2035 set at last year’s COP29 talks in Azerbaijan. Poorer countries had been looking for $1.3 trillion.

The White House has not publicly disclosed whether the US will have an official role at the Belem talks. Given Trump’s courting of fossil fuels and antagonism towards curbs on industry, activists fear a US presence would stall efforts by other countries on climate change.

The Pacific nation of atolls and islands – at risk of disappearing under rising sea levels – is exploring novel initiatives before the next COP

The COP climate meetings have become more like a “festival for the oil-producing countries,” Maina Talia, Tuvalu’s minister of climate change, told Al Jazeera.

The Pacific nation of atolls and islands – at risk of disappearing under rising sea levels – is exploring novel initiatives before the next COP, such as creating the world’s first fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty.

Colombia has offered to host the first international conference next year for such a treaty, to which about 16 countries have signed up.

A human-made climate crisis

Some 39 small island countries, which are home to about 65 million people, already need $12 billion a year to cope with climate change, says a report by the Global Center on Adaptation released last week.

Displaced communities should be compensated for the loss and damages they suffered because of a human-made climate crisis

Displaced communities should be compensated for the loss and damages they suffered because of a human-made climate crisis

By 2050, sea levels could rise by up to 30 centimetres, putting many health facilities underwater, warns the World Health Organisation. “The climate crisis amplifies existing health risks, including heatstroke during record-breaking heatwaves, triggering disease outbreaks after floods, exacerbating hunger from disrupted food systems,” it says.

Tuvalu reached a co-operation accord with Australia in 2023 that included the world’s first climate change migration visa. But last year Australia offered a visa programme for only up to 280 people a year from Tuvalu in the context of climate change, said Amnesty International.

The human rights group cited the landmark ruling by the International Court of Justice in July, saying countries are legally obligated to curb emissions and that human rights cannot be ensured without protection of the climate system.

“States have a responsibility to cooperate to prevent further displacement and ensure that people can remain in their homes,” said Amnesty. “Displaced communities should also be compensated for the loss and damages they suffered because of a human-made climate crisis.”

Promises by richer countries to dig deep in their pockets look unlikely to be realised soon.