Critics who warned last year that a European Union minerals pact with Rwanda would inflame instability in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo were vindicated last week when Rwanda-backed rebels captured the city of Goma.

The EU is now facing calls to suspend the pact struck with Rwanda last February. It aims to ensure a secure stream of critical minerals used in smartphones, electric cars and green technologies amid competition with China.

But it was hardly a secret that most of the minerals exported from Rwanda actually originate from eastern Congo, where more than 100 armed groups have vied for control and millions of people pay the cost, suffering mass rapes and kidnappings as well as mass displacement and acute food insecurity.

With the world focused on President Donald Trump, Rwanda, the darling of the west for its efficient handling of aid and reform, embarked on a stealth occupation of eastern Congo, culminating on 26 January with the capture of Goma, the provincial capital of North Kivu that is only 100 km from the Rwandan capital Kigali.

Around 4,000 Rwandan troops accompanied rebels from the Congolese March 23 Movement (M23), say reports. DRC's government called the takeover a "declaration of war” as M23 appeared to be advancing towards Bukavu in South Kivu and even threatening to march “all the way to Kinshasa,” the DRC capital 1,500 km away.

Rwanda has denied supporting M23. But Jean-Pierre Lacroix, chief of UN peacekeeping, said the Rwandan army is in "de facto control of M23 operations”. “There was no question that there are Rwandan troops in Goma supporting the M23,” he said.

Parallel administration

A report for the UN’s Group of Experts last year said M23 had established a “parallel administration” controlling mining activities and trade in the DRC, exporting at least 150 tons of coltan to Rwanda.

The UN also estimates M23 gets about $300,000 a month in revenue through its control of a mining territory in eastern DRC. Rwanda, meanwhile, recorded $1.16 billion in mineral exports in 2023, a sum that is similar to that claimed by the DRC in lost revenues from gold, tin, tantalum and tungsten illegally smuggled by Rwanda.

Rwanda should not export what it does not own nor use the proceeds to equip their armies and fund their expansionist aims in the Congo, said Felix Tshisekedi, DRC president. “Rwanda continues to hide behind the M23, which is why I do not discuss with this terrorist group,” he said after the EU-Rwanda deal was agreed.

Critics say the EU deal was struck out of guilt for failing to stop the 1994 genocide of Tutsis

Critics say the EU deal was struck out of guilt for failing to stop the 1994 genocide of Tutsis and that it has helped to cover and advance Rwanda’s territorial ambitions.

Brussels and Kigali signed the “Memorandum of Understanding” in February 2024 to ensure a "sustainable supply of raw materials" for the EU, in exchange for funding to develop Rwanda’s mineral supply chains and infrastructure.

The deal is part of the EU’s Global Gateway, a €300-billion infrastructure programme to ensure investment through partnerships with countries around the world, including mineral-rich countries such as the DRC.

“Greater Rwanda”

The area of current conflict in the Congo is rich with coltan, gold, tin, tantalum, cassiterite, tungsten, niobium and other “blood minerals” and rare earths.

The EU also supports Rwandan forces in Mozambique, giving €20 million under the European Peace Facility last November to face an Islamic insurgency in Cabo Delgado province, where French energy company TotalEnergies is developing gas deposits.

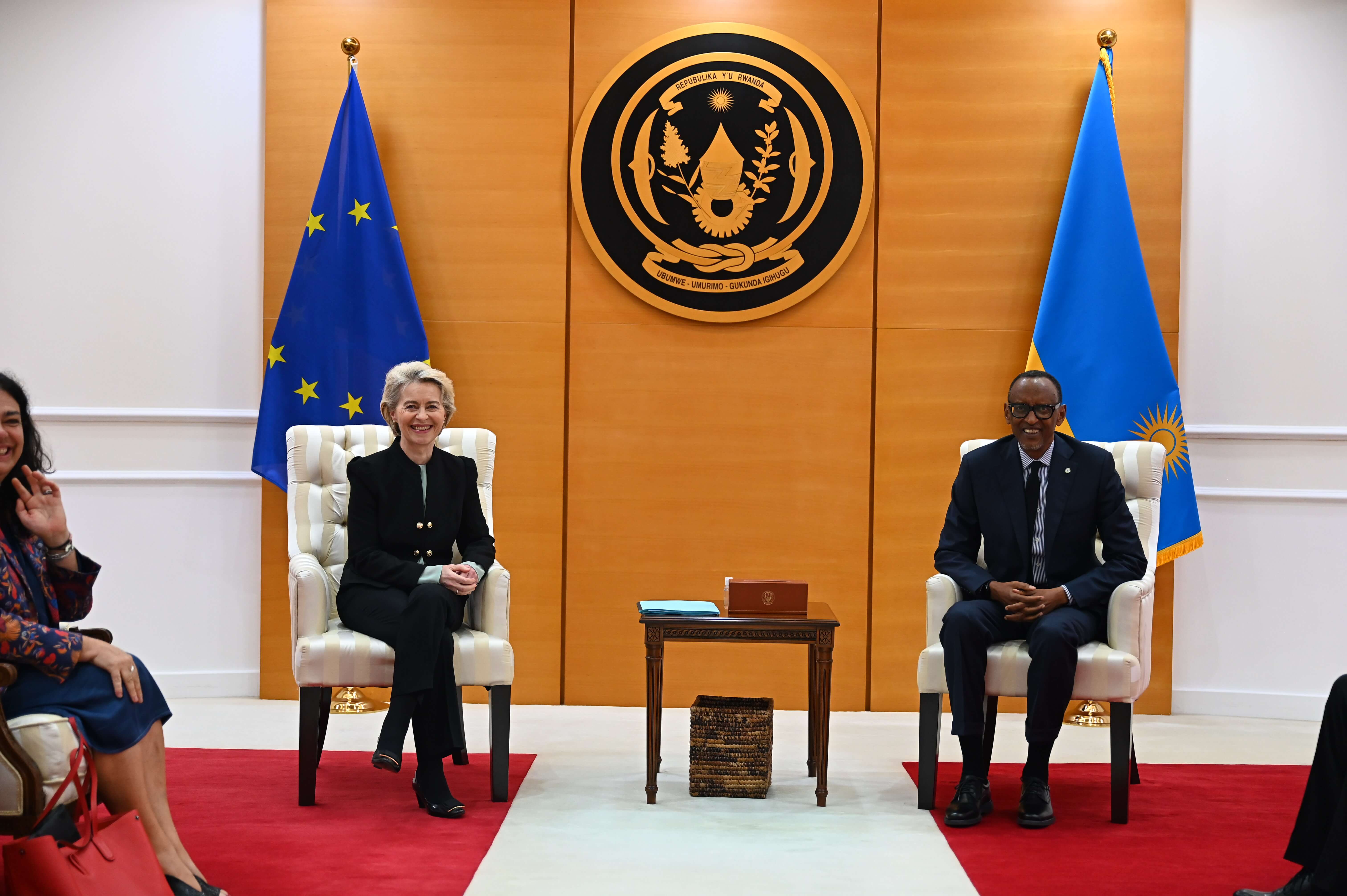

The EU also supports Rwandan forces in Mozambique - Ursula Von der Leyen with President Paul Kagame of Rwanda

The EU also supports Rwandan forces in Mozambique - Ursula Von der Leyen with President Paul Kagame of Rwanda

The Kivu provinces in the DRC were “unjustly” withheld from Rwanda by European colonial powers who drew the region’s borders, James Kabarebe, Rwanda’s minister of state for regional co-operation, recently said. Meanwhile, talk of a “Greater Rwanda” appears to have ramped up.

Ethnic tensions in the region have simmered during the last 30 years and broken out into two major wars in the late 1990s and the early 2000s.

Rwanda’s Tutsi-led government, led by President Paul Kagame, says minority Tutsis in eastern Congo need to be protected from a Hutu rebel group created by former leaders of the Rwanda genocide, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda. M23 has also been battling pro-government militias known as Wazalendo.

Will the EU act?

The name M23 refers to its claim the DRC government failed to honour a peace agreement signed on 23 March 2009. The group emerged in 2012 and has gained momentum in the last couple of years while Western calls on Kigali to end support went ignored.

When M23 briefly took over Goma in 2012, the administration of former president Barack Obama led global criticism, and the US, EU and UK halted some aid to Rwanda. Since then, Rwanda’s popularity with western officials led to it being touted by the UK Conservatives as a place to transfer asylum-seekers from the UK, and a similar plan was raised in Germany last September.

Now, an upsurge in violence threatens to draw in neighbours across the Great Lakes region and beyond, including Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa. Rwanda has also made overtures to countries such as Turkey and Qatar as Western opinion cools.

The UK has suggested suspending aid to Rwanda, while Germany has cancelled meetings and said it was in talks with other donors about “further measures”. “We have levers and we have to decide how to use them,” said Bernard Quintin, foreign minister of Belgium, the DRC’s former colonial power.

The Congolese people are waiting to see if the EU will act but perhaps not holding their breath.