An agreement announced in October between the UK and Mauritius over the future of the disputed Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean was hailed as a win for all the parties involved.

Barely two months on and the terms of the deal are in doubt, following a change of government in Mauritius and the election of Donald Trump to a second term in the White House.

US interest hinges on the fact that its main strategic asset in the region is its military base on the largest island of the Chagos archipelago, Diego Garcia. It currently leases the base from Britain and would retain it under the terms of the October agreement that cedes the islands to Mauritius.

While the new government in Port Louis takes time to review the deal, there has been considerable political posturing on both sides of the Atlantic over whether its terms amount to a surrender by Britain’s Labour government that ultimately serves Chinese rather than Western interests in the region.

Critics include Britain’s Conservative ‘China hawks’ as well as members of the Trump camp who baulk at a deal in which Britain hands sovereignty of such strategic real estate to Mauritius, which they brand a Chinese ally.

Nigel Farage, the leader of the UK’s right-wing Reform party, has been talking up US opposition to the Chagos deal, claiming the incoming administration is “appalled”. He said a senior Trump adviser had told him Diego Garcia was “the most important island on the planet” for the US.

Even before the US election, Marco Rubio, Trump’s pick for secretary of state, warned that the Chagos deal posed a serious threat to US national security interests in the Indian Ocean.

Which side is right?

That is in contrast to the Biden administration, which welcomed the agreement, having backed the negotiations that led to it. So did India, where the foreign ministry also pledged to work with its partners in strengthening maritime safety and security in the Indian Ocean region.

Which side is right? And what are the possible consequences of negative US reactions to the deal now that the government in Mauritius has, for the time being, put it on hold?

The dispute dates back more than half a century to 1965, when the UK hived off the Chagos Islands from its then colony of Mauritius, 1,300 miles to the southwest. The motivation was to provide for a US base at Diego Garcia after Mauritian independence, which came in 1968.

The UK would remain in effective control of Diego Garcia for an initial period of 99 years

In their joint statement on October 3, the UK and Mauritian governments announced an agreement in which the UK would recognise Mauritian sovereignty over the archipelago, including Diego Garcia.

The UK, however, would remain in effective control of Diego Garcia for an initial period of 99 years to ensure the continued operation of the US-UK base, described in the statement as playing a vital role in regional and global security.

The very next day, the Mauritian prime minister, Pravind Jugnauth, announced legislative elections for November 10, perhaps hoping to profit politically from a positive deal with the UK.

Sell-out

In the event, his scandal-hit administration was unseated in a landslide victory for the Change Alliance of former prime minister Navin Ramgoolam.

Having described the Chagos deal as a ‘sell-out’ during his campaign, Ramgoolam said after taking office that he had requested an independent review of what he described as the confidential draft agreement with the UK.

Further clarification of the new Mauritian position could therefore emerge in the coming days

He expressed reservations about the agreement in a late-November meeting with Jonathan Powell, the UK national security adviser, but agreed to get back to the British side within two weeks after a legal review of its terms. Further clarification of the new Mauritian position could therefore emerge in the coming days.

The new prime minister may simply be pressing for a more advantageous agreement than one that already includes unspecified payments for continued use of the Diego Garcia base. Any final arrangement would be subject to a treaty between the two sides.

Win for all

In the interim, the UK’s Labour government has been defending its position, pointing out that negotiations with Mauritius were initiated two years ago by the previous Conservative administration.

The UK’s priority has been to maintain the Diego Garcia base while bringing the status of the archipelago within the ambit of international law.

In 2019, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion that British rule of the Chagos archipelago was unlawful and should be ended as rapidly as possible. The decision was backed by a large majority of the United Nations General Assembly.

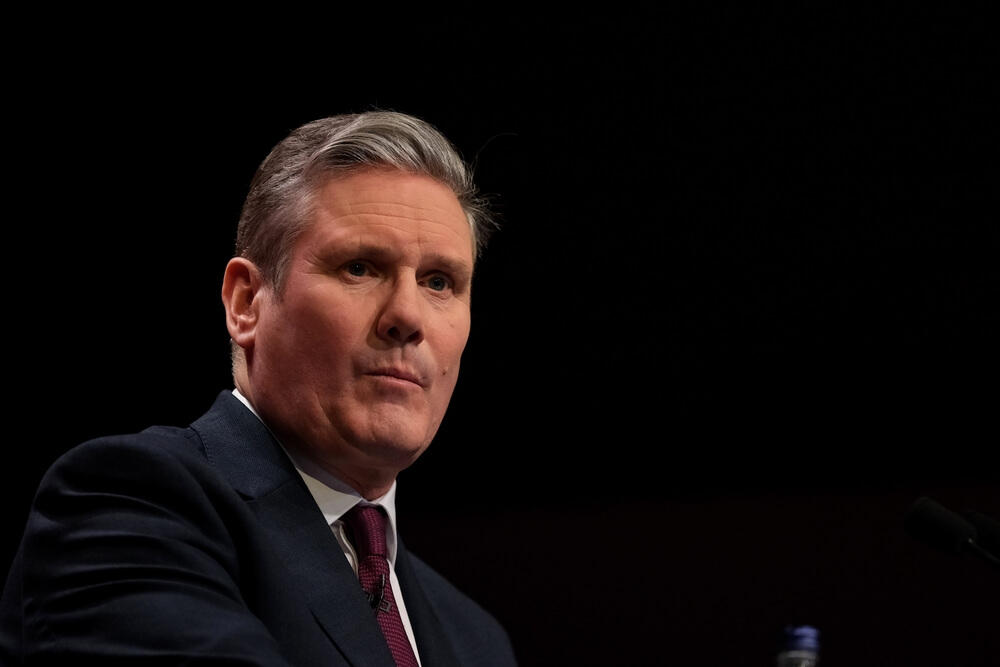

The single most important thing was ensuring that we had a secure base, the joint US-UK base; hugely important to the US, hugely important to us - Keir Starmer

The single most important thing was ensuring that we had a secure base, the joint US-UK base; hugely important to the US, hugely important to us - Keir Starmer

Responding to critics of the agreement, Prime Minister Keir Starmer said: “The single most important thing was ensuring that we had a secure base, the joint US-UK base; hugely important to the US, hugely important to us.”

Pending a possibly revised agreement with Mauritius, he must now persuade Trump that he has secured the best deal. A key US concern will be to secure continued access to the Diego Garcia for its nuclear fleet, given that Mauritius is a signatory to an Africa-wide nuclear weapon-free zone treaty.

The perception that may have emerged in the US of Mauritius being a passive client of China is something of a caricature, despite their close economic and trade ties.

The relatively prosperous island state, with a population of 1.3 million, the majority descendants of indentured labourers who moved there from India in colonial days, remains closer to New Delhi than Beijing.

Since independence, its democratic politics have been largely dominated by the Ramgoolam and Jugnauth families.

It was the current prime minister’s father, Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, who as chief minister of the pre-independence administration, agreed to detaching the Chagos Islands from Mauritius as part of an independence deal.

It will partly be up to his son to decide on the terms on which the islands will be restored in a deal that can still be viewed as a win for all.