Recent statements from a UK government struggling to contain a ballooning benefits bill risk reinforcing a long-standing prejudice that the British are a nation of work-shy malingerers.

With the number of working-age people off the payroll because of long-term sickness at a near-record level of almost 3 million, the government’s Back to Work strategy has honed in on those claiming to be suffering from chronic mental health conditions.

Trailing the latest crackdown on disability payments, the work and pensions secretary Mel Stride this week pondered whether some claimants were merely experiencing “the kinds of ups and downs of life that are part of the human condition”.

The government has been widely accused of victim-blaming since Prime Minister Rishi Sunak pledged last month to address a “sick note culture” in which millions were being unnecessarily written off work and into welfare.

Critics who range from health charities to opposition politicians say blame for the long-term sickness crisis lies with the government rather than with the feckless public. They cite long waiting lists for health care which the government has yet to tackle.

The government’s case has hardly been strengthened by the defection of former Conservative health minister Dan Poulter to the opposition Labour party. The parliamentarian and practicing psychiatrist said he believed only Labour could be trusted to restore a national health service that best met the needs of every patient.

International concerns

The context of the present health benefits debate is Britain’s apparent failure to match similar economies in restoring the workforce to pre-Covid levels.

G7 data indicates that the UK is the only member of the club of leading developed nations where the share of working-age people outside the workforce remains higher than before the pandemic. The UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility blamed that situation on ill-health being consistently a bigger factor than in the other advanced economies.

How far is the Sick Britain scenario a true picture of the country? Or is the government falling back on blaming a large slice of the electorate for its own policy failings?

The phenomenon has even ignited international concerns and will figure on the agenda of International Monetary Fund inspectors due in the UK this month for an annual economic assessment.

Helge Berger, deputy head of the IMF’s European division, has said the rise in working age inactivity was a cause for concern in terms of economic growth. “One area to think about is the quality of health care. Another is the way disability is supported,” The Guardian quoted Berger as saying.

So how far is the Sick Britain scenario a true picture of the country? Or is the government falling back on blaming a large slice of the electorate for its own policy failings?

Vacuous appeals

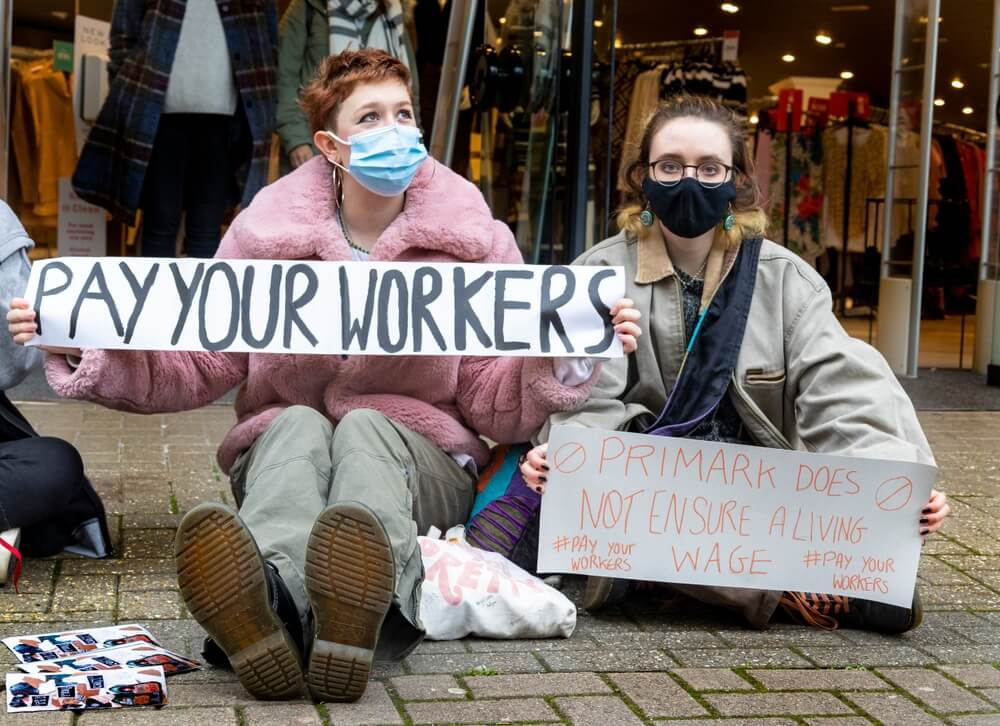

There has been a recurring trend to blame the workers - or, in this case, the non-workers - for the country’s economic ills, including low productivity. This is often fuelled by negative headlines about benefit scroungers.

A 2012 book by five Conservatives, including the then future Prime Minister, Liz Truss, perhaps best illustrates the syndrome.

“Once they enter the workplace, the British are among the worst idlers in the world,” according to Britannia Unchained. “We work among the lowest hours, we retire early and our productivity is poor.”

Vacuous appeals from politicians of all parties to “hard-working families” can be just as irritating but are less offensive than implying that those suffering from long-term depression and other debilitating conditions are simply work-shy

A similar attitude was reprised by Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who was revealed to have told officials during the Covid crisis that Britain’s “malingering work-shy people” needed to get back to work.

Unlike some of his successors, Johnson at least had the good sense to keep his comments confidential until they were revealed in the course of a Covid inquiry.

Appearing to cast voters as the villains may not be a good look so close to an election. Vacuous appeals from politicians of all parties to “hard-working families” can be just as irritating but are less offensive than implying that those suffering from long-term depression and other debilitating conditions are simply work-shy.

Pioneers in transforming the world of work

There is no doubt that the rising benefits bill presents a challenge to this and future governments. Overall payments in incapacity and disability benefits are inexorably set to rise despite the government’s intention to get the sick back to work, if only part-time.

The sickness benefits furore has inevitably become embroiled in a wider debate about the working public’s evolving attitude to the workplace.

The British, more than most, appear to have embraced a work-from-home culture established during the pandemic, despite the exhortations of politicians for civil servants and other office workers to get back to work.

For many, it is an economic choice. In the face of high travel costs and crippling child-care payments, it makes sense to redress the home-office balance. Others are taking advantage of the fluidity of the growing gig economy to change their work-life ratio in favour of the latter.

There is a recognised tendency among younger, more educated Britons towards “quiet quitting” - a preference for fulfilling their tasks with a minimum of office face time and extra unpaid hours

There is a recognised tendency among younger, more educated Britons towards “quiet quitting” - a preference for fulfilling their tasks with a minimum of office face time and extra unpaid hours

Just like the heads of the companies and organisations who employ them, people tend to make rational decisions according to the challenges they face.

Beyond the Back to Work rhetoric, the current government appears to recognise the choices some people face. A law adopted last year gives people the right to request predictable working patterns and seeks to erradicate unfair practices in zero-hour contracts, seen as an important element in the UK’s flexible labour market.

Although British workers have traditionally worked as many or more hours than their European counterparts and often retire later, there is a recognised tendency among younger, more educated Britons towards “quiet quitting” - a preference for fulfilling their tasks with a minimum of office face time and extra unpaid hours.

In another workplace indicator, a large majority of UK companies that joined a trial of the four-day week in 2022 have stuck with an arrangement that is said to have positively contributed to employees’ physical and mental health and work-life balance.

Rather than Britain’s workers being the loafers of popular imagination, they may be emerging as pioneers in transforming the world of work in an era when lifetime careers are no longer guaranteed and AI threatens the future of a multitude of jobs.

Politicians might do better to plan for an evolving world of work and meanwhile to focus on improving the health prospects of the long-termed unemployed rather than forcing them back to work before they are fully able.