Latest population figures indicate that the UK is bucking the trend in a Europe that is confronting the economic challenges of demographic decline.

The Office for National Statistics reported this month that the British population reached 68.3 million by mid-2023, one per cent higher than a year before and the fastest rate of growth since 1971.

There was one important caveat, however. The increase was entirely due to inward migration in a period that actually saw deaths exceed births and the fertility rate further tumble.

From an economic perspective, the figures could be good news.

The investment bank Morgan Stanley this week forecast that the UK was the only European country set to expand thanks to shifting demographics and was on course to increase GDP by four percentage points by 2040.

By contrast, the impact of an aging population and falling birth rates could shave four per cent off Eurozone GDP by the same year.

It would seem, then, that there are two routes ahead towards a demographic Goldilocks zone in which the population total is neither too small nor too big, but just right. Either the politicians and the planners persuade families to have more babies or they allow in more immigrants.

The two routes

Both are fraught with difficulties. More than half the British public think the rate of immigration is too high, variously arguing that newcomers are threatening the nation’s identity or, more mundanely, that there is simply not enough room.

Meanwhile, many women are declining to breed, seemingly oblivious to their national duty to keep the numbers up. They should be having 2.1 babies to keep the British-born population stable, while the latest figures show the fertility rate in England and Wales has fallen to 1.49.

Humanity’s sages have been wrestling for millennia with the challenges of demographics, even if they did not call it that. They have often faced the obduracy of actual humans who, where possible, have made their own decisions about whether to breed or not to breed.

What most philosophers, planners, politicians and statisticians who have addressed the population challenge have in common is that they frequently got it wrong

Plato proposed that, in the ideal city state, the population could be kept at a suitable level, if necessary, by infanticide. Troubled by a slowing of population growth in imperial Rome, Augustus introduced measures to punish celibacy and reward large families. They had little effect.

Much later, the 18th century English economist Thomas Malthus warned of the consequences of unchecked population growth. "The power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man,” he wrote.

Unlike the beasts of the fields, rational human beings might consider the consequences of their reproductive potential and curb their natural drive, he proposed.

What most philosophers, planners, politicians and statisticians who have addressed the population challenge have in common is that they frequently got it wrong.

Population control measures

In the 1960s, humanity was invited to panic about the onslaught of an apocalyptic population explosion that would force hundreds of millions into starvation in the ensuing decades. The American biologist Paul Ehrlich predicted, among other things, that: “England will not exist in the year 2000.”

In the same decade, President Charles de Gaulle was optimistically forecasting that France’s population was set to rise to 100 million (it currently stands at around 68 million). In pro-natalist France, contraception was outlawed until 1967.

If even draconian measures to reduce populations do not always work as they should, how much harder will it be in modern democratic societies to encourage families to have more children?

Where population control measures have been instituted, they have brought unintended but possibly predictable consequences. China’s one-child policy, abandoned in 2016, had the desired effect of reducing the number of births but it also led to a growth in the proportion of older people and a sex ratio that favoured male births.

These examples do not bode well for European governments facing declines in their working-age populations, expected to shrink by a further 6.5 per cent by 2040.

If even draconian measures to reduce populations do not always work as they should, how much harder will it be in modern democratic societies to encourage families to have more children?

Growing pro-natalist rhetoric

The only feasible way is through financial incentives, perhaps coupled with the persuasive tactics of what psychologists term “nudge theory”. But how do you nudge women, on whom most childcare still devolves, to abandon financially rewarding careers and stay at home to look after the family?

As for financial incentives, in the UK as elsewhere there is really not much spare cash to go around. In a country where austerity is already blamed for a declining birth rate, setting aside more funds for benefits and childcare would put yet more pressure on a tight budget.

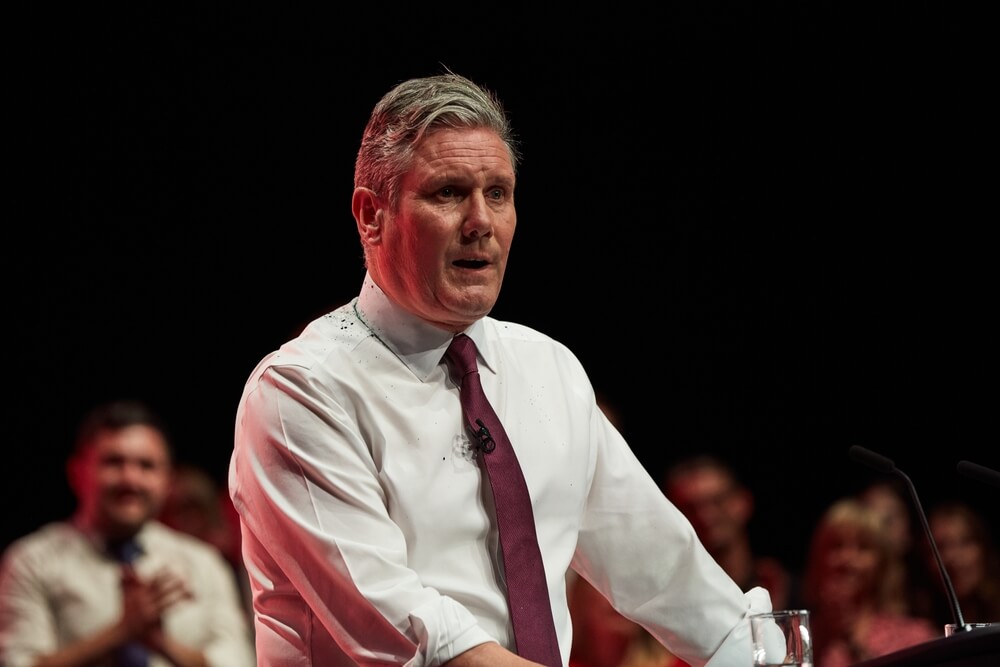

Keir Starmer faced his first Labour Party rebellion within weeks of coming into office over his failure to remove a benefit cap that restricts support to a family’s first two children

Keir Starmer faced his first Labour Party rebellion within weeks of coming into office over his failure to remove a benefit cap that restricts support to a family’s first two children

Prime Minister Keir Starmer faced his first Labour Party rebellion within weeks of coming into office over his failure to remove a benefit cap that restricts support to a family’s first two children.

At the same time, his government has pledged to reduce net migration, although it tends to benefit the public finances.

Given the current birth rate in the UK, the country will continue to be dependent on immigration if it wants to sustain a healthy economy. So expect to hear growing pro-natalist rhetoric from the right and far right, encouraging the ‘indigenous’ population to breed.

Perhaps the most honest assessment of the future comes in a parliamentary briefing paper published in July: “The number of future deaths can be projected with the most accuracy, but the number of future births is relatively uncertain and net migration is all but impossible to forecast accurately.”