The latest 2025 annual survey by a leading international consultancy rated London as the world's top city for the tenth year in a row.

The British capital scored high for prosperity and livability and took the top spot in something called the lovability index, beating rivals such as Paris and New York.

The image created by the World’s Best Cities report, drawn up by the tourism and economic development consultancy Resonance in conjunction with the Ipsos polling organisation, was in stark contrast to a current fashion for portraying London as a city in decline.

To judge from the outpourings of the media commentariat, many of them London-based, the World’s Best City is a polyglot dystopia from which even millionaires are fleeing to escape the twin evils of tax and crime.

The trend reached its apogee in a diatribe this month from The Telegraph’s Isabel Oakeshott, recently returned from living in Dubai. She conceded that, to the casual eye, the capital certainly looked splendid in the sunshine, “but the rampant crime and aggressive promotion of foreign cultures and causes is impossible to ignore”.

In an article that focused on the contribution of a “tidal wave” of uncontrolled immigration to the UK’s alleged decline, Oakeshott wrote of London’s Thameside Embankment:

“I watched as a Rastafarian swaggered down the middle of the road, high as a kite on God knows what. He was waving two gigantic Palestinian flags – far more prolific, it seems, in town centres these days than the Union Jack.”

These and similar portrayals reinforce the concept that all great cities are not just places but also a state of mind. Whether it is Cairo, Los Angeles or Rome, provincials and other outsiders tend to regard them with an equal mix of contempt and awe.

Given the UK’s political divisions and a national mood of economic stagnation, the image of a wealthy but dysfunctional London has emerged as a useful symbol in the nation’s culture wars.

Once despised as the Big Smoke in the days when it was dirty, bomb-battered, and poor, London is now portrayed, not just as the refuge of drug-crazed Rastafarians, but also as the lair of a self-satisfied cosmopolitan liberal elite that is throwing the country to the dogs.

Most diverse and inclusive city in the world or just getting worse?

Prominent in this supposed metropolitan cabal are Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who represents the inner London constituency of Holborn and St. Pancras, and Sadiq Khan, the capital’s twice-elected Labour mayor.

Starmer’s Conservative predecessor, Rishi Sunak, once castigated the future prime minister as a politician who “rarely leaves north London”.

Khan and his Muslim co-religionists have meanwhile, been accused of putting a dampener on London nightlife and pub culture.

Referring to Khan in a Spectator magazine article headlined ‘London is getting worse’, author Sean Thomas wrote, “For a decade London has been led by a beige, joyless, teetotal homunculus, a man so dedicated to Not Having Fun he bans bikini ads from the Tube.”

London had plunged nine places in its Global Livability Index since last year alone

As a Devon-born provincial who made London his home, Thomas’s views might not be typical of its almost nine million population.

Time Out magazine ran a survey last month that found more than seven out of ten Londoners agreed that they lived in the most diverse and inclusive city in the world.

The survey noted that around 300 languages were spoken throughout the capital, while an estimated 41 percent of its inhabitants were born outside of the UK.

Surveys can, of course, point in different directions. In the same month, Time Out quoted the Economist Intelligence Unit as determining that London had plunged nine places in its Global Livability Index since last year alone.

Tired of London, or tired of life?

Like all great cities, London is a mixture of benefits and challenges that are constantly evolving. Current gripes centre on the cost of living in a city where sky-high rents and house prices have made life precarious, particularly for the young.

Taking the longer view, however, the UK capital has successfully emerged from an actual decades-old decline.

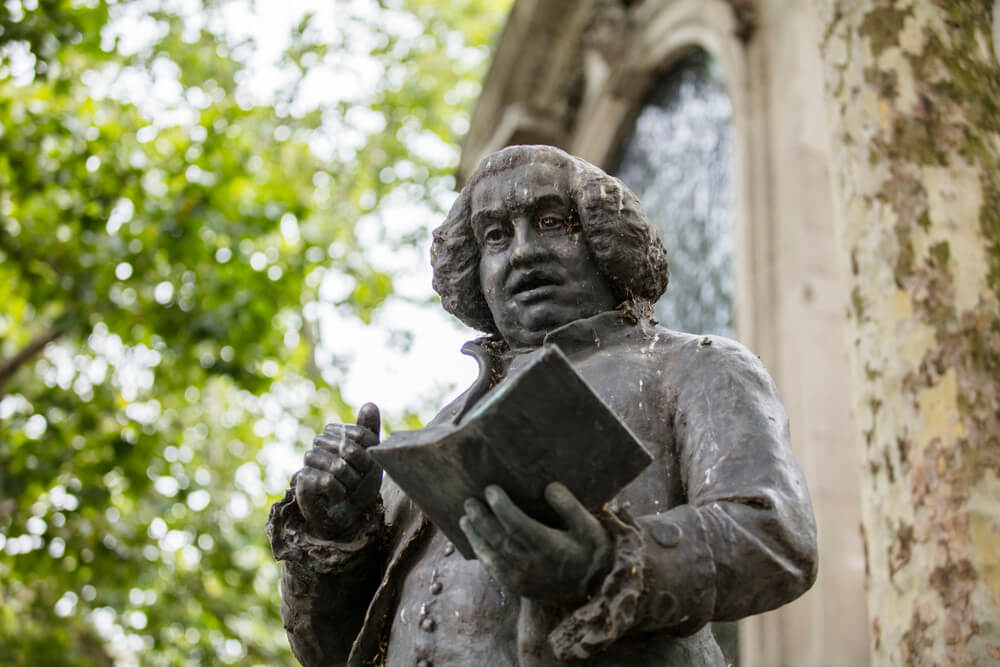

When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life, for there is in London all that life can afford - Dr Samuel Johnson

When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life, for there is in London all that life can afford - Dr Samuel Johnson

Only in the last decade or so did it recover the population it boasted in 1939. That was before wartime dislocation, followed by the collapse of its industrial base and docklands, saw its numbers plunge to less than seven million in the 1980s.

It could be argued that London, like other global metropolises, has actually been too successful in contrast to regions that have in many cases been left economically behind.

Reflecting on Resonance’s Best Cities findings, its Ipsos partner said London’s tenth successive win demonstrated the capital’s enduring global appeal in the face of economic and political headwinds.

According to the polling organisation, “The city's rich history, vibrant arts scene, and diverse culinary offerings continue to draw visitors and residents alike.”

The political right’s current antipathy to the cosmopolitan capital is just the latest manifestation of a historical love-hate relationship between the city and a country it can sometimes appear to both ignore and dominate.

There will always be those like the 19th century rustic curmudgeon, William Cobbett, who dismissively labelled London as the Great Wen.

Others will continue to abide by Dr Samuel Johnson’s dictum that “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life, for there is in London all that life can afford.”