US President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs may have been “paused” almost immediately after their introduction in April – a reprieve just recently extended until August 1, but they sent a clear message: countries around the world must adapt to a new era of coercive economic diplomacy.

Choosing sides in a superpower competition is not the approach most governments are taking.

For China, Trump’s actions – which have severely undermined trust in the United States – look like an opportunity to strengthen its global influence.

To that end, the country has ramped up its charm offensive, with President Xi Jinping visiting Cambodia, Malaysia, and Vietnam – which China calls “victims” of US tariffs – to strike bilateral deals spanning health, technology, agriculture, and education.

China also lifted some sanctions against the European Union, which is reeling not only from Trump’s tariffs, but also from his evident lack of commitment to NATO.

And, in a meeting with his Nigerian counterpart, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi pledged to work with African countries to “reject protectionism,” “oppose … bullying,” and defend “fairness and justice.” “China will provide certainty to this uncertain world,” Wang declared.

The geostrategic swing

Many of these governments are not opposed to closer cooperation with China, and may welcome the opportunity to show the US that they have options.

But there is little reason to expect the geostrategic swing towards China that Xi’s government is attempting to engineer. After all, China has its own record of coercive diplomacy.

Notably, China has gained effective control over the flow of rare-earth minerals, which are crucial to myriad modern technologies, from smartphones to wind turbines to medical devices.

China has demonstrated a pattern of curbing imports from countries with which it has disagreements

In 2010, China halted exports of rare earths to Japan for two months over a fishing dispute. In April, it suspended such exports almost entirely, highlighting its ability to weaponize critical supply chains.

Similarly, China has demonstrated a pattern of curbing imports from countries with which it has disagreements, often under the guise of enforcing health and safety standards.

Hedged globalization

Rather than replace one coercive power with another, countries are embracing “hedged globalization,” whereby they cultivate networks of diverse partnerships that limit their exposure to either superpower. Southeast Asia – a key front in the US-China rivalry – is leading the way.

Mindful of their historical divisions and territorial disputes, leaders of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries have long sought to bolster peace and stability through cooperation.

But this effort has lately gained new impetus. In the 2025 State of Southeast Asia survey, a majority of respondents expressed support for strengthening intra-ASEAN ties.

Intra-regional ties are only part of the hedging agenda

But intra-regional ties are only part of the hedging agenda. Nearly 52% of State of Southeast Asia respondents now view the EU as the region’s second most trusted non-regional partner (after Japan), up from 41.5% last year and surpassing the US.

As Singapore’s deputy prime minister, Gan Kim Yong, put it at the recent Nikkei Forum on the Future of Asia, beyond “doubl[ing] down on regional integration,” Asia must “form agile partnership with like-minded partners.”

In addition to deeper engagement with the EU, Singapore is eyeing opportunities with Chile, Peru, and Mercosur (comprising Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay), deeper cooperation with the Gulf Cooperation Council, and the strengthening of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Similarly, South Korea’s newly appointed trade minister has a history of advocating the country’s participation in the CPTPP, which includes neither the US nor China (though the latter has sought membership). This represents not only a desire for expanded market access, but also a commitment to rules-based – rather than deal-oriented – globalization.

Leadership is vital

Canada is also becoming increasingly alienated from the US, owing to Trump’s tariffs, calls for it to become the 51st US state, and personal insults.

But Canada will not soon forget China’s forceful retaliation for its 2018 arrest (at the request of the US) of Meng Wanzhou, a senior executive of the Chinese tech giant Huawei.

China imposed tariffs on several imports from Canada; suspended imports of Canadian beef altogether; and detained two Canadian nationals.

The “two Michaels” were held for nearly three years – as long as it took for the US to agree to release Meng.

To avoid depending on either coercive superpower, Mark Carney has been championing trade accords with ASEAN, the EU, and Mercosur

To avoid depending on either coercive superpower, Mark Carney has been championing trade accords with ASEAN, the EU, and Mercosur

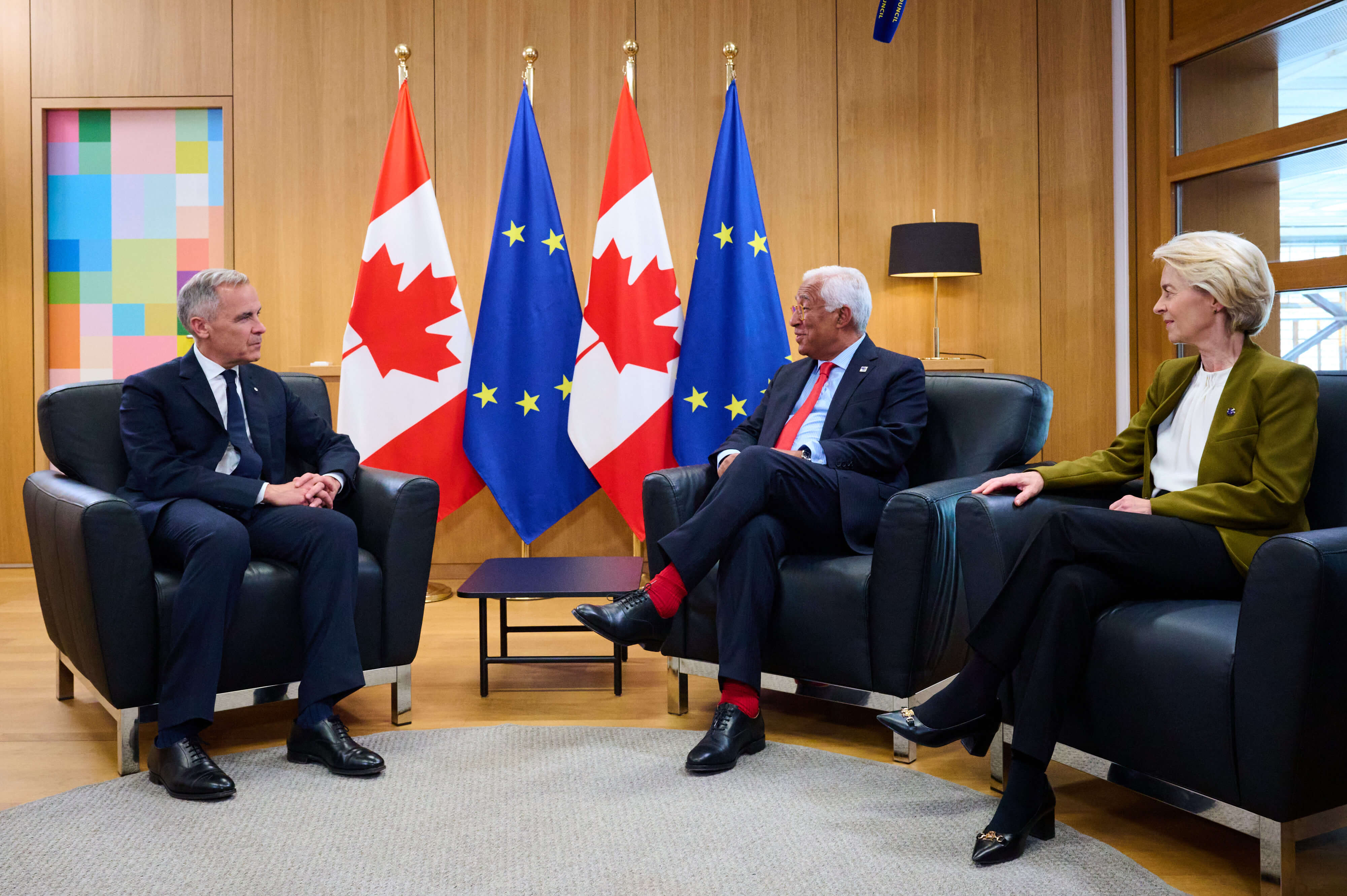

To avoid depending on either coercive superpower, Prime Minister Mark Carney has been championing trade accords with ASEAN, the EU, and Mercosur.

And within Latin America, Brazil and Mexico are choosing to set aside their historic rivalry to forge deeper bilateral cooperation.

The same goes for America’s other closest ally, the EU, whose quest for “strategic autonomy” reflects a clear desire to reduce its dependence on both the US and China, while protecting itself from threats posed by Russia.

Moreover, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has championed stronger trade and investment links with ASEAN and the CPTPP, noting that such steps would boost Europe’s economic security.

Sweden is calling for the EU to become a full member of the CPTPP – a step that would create a free-trade area accounting for nearly 30% of global GDP.

The emergence of hedged globalization reflects most countries’ desire to be insulated from today’s superpower competition.

While they may make concessions to avoid tariffs and sanctions in the short term, they will also work hard to reduce their vulnerability to such threats.

But if a system based on hedged globalization is to work, leadership is vital. This is where middle powers come in: they must work together to uphold rules-based engagement, create space for smaller states to advance their interests, and act as a stabilizing anchor for the global economy.

Only then can countries avoid behind held hostage by the world’s superpowers, and instead forge their own paths with partners who share their desire for an open and stable economic order.

Yeling Tan, Professor of Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford, is a nonresident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.