The reputation of the UK as a pioneer of free healthcare for all is at risk from a funding and staffing crisis that is turning the country into the sick man of Europe.

With a record 7.8 million people on waiting lists for treatment ahead of what health providers say could be their toughest winter ever, the problems facing the National Health Service (NHS) now threaten to undermine recovery in the wider economy.

Latest statistics point to a record two and a half million people out of work because of unresolved long-term health problems after the NHS itself suffered 27 million lost shifts in 2022 because of staff sickness.

Health care leaders this month cited staff burnout, funding squeezes, workforce strikes and rising demand for care as among the factors confronting the sector.

It is a trend that alarms those in the sector who fear that the current failings of the NHS will lead to the default privatisation of health provision and the emergence of a divisive two-tier system of care.

A decade of underfunding

Like comparable economies, the UK is still recovering from the unprecedented pressures imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic. But the challenge it faces is compounded by more than a decade of underfunding, linked to austerity policies.

Going into the pandemic, the UK already had fewer doctors and nurses per head of the population, fewer hospital beds, and lower per capita spending than many of its neighbours in Europe. While some of its hospitals are crumbling, new ones that were promised remain unbuilt.

Improving the NHS now figures among the headline priorities of both the main political parties, although neither is promising a simple or painlesss fix in a period of relatively high inflation and low growth.

Proposals from both parties are likely to involve some greater level of involvement by the private sector

Ahead of an election within a year, proposals from both parties are likely to involve some greater level of involvement by the private sector, either as direct providers of healthcare services or as investors in medical innovation and infrastructure.

But how does that square with the attitudes of successive generations who have benefitted from publicly provided health care, free whenever needed from the cradle to the grave?

Surveys indicate that, while satisfaction with the NHS is at an all-time low of just under 30 per cent, the overwhelming majority of the public, 9 out of 10, continue to support the principles on which it was founded 75 years ago.

Free universal healthcare is so embedded in the national psyche that it has been described as the nearest thing secular and multicultural Britain has to a shared religion.

That was reflected in the starring role assigned to the NHS at the opening ceremony of the London Olympic Games in 2012 and by those who stood at their doorsteps a decade later to applaud the doctors and nurses battling the Covid pandemic.

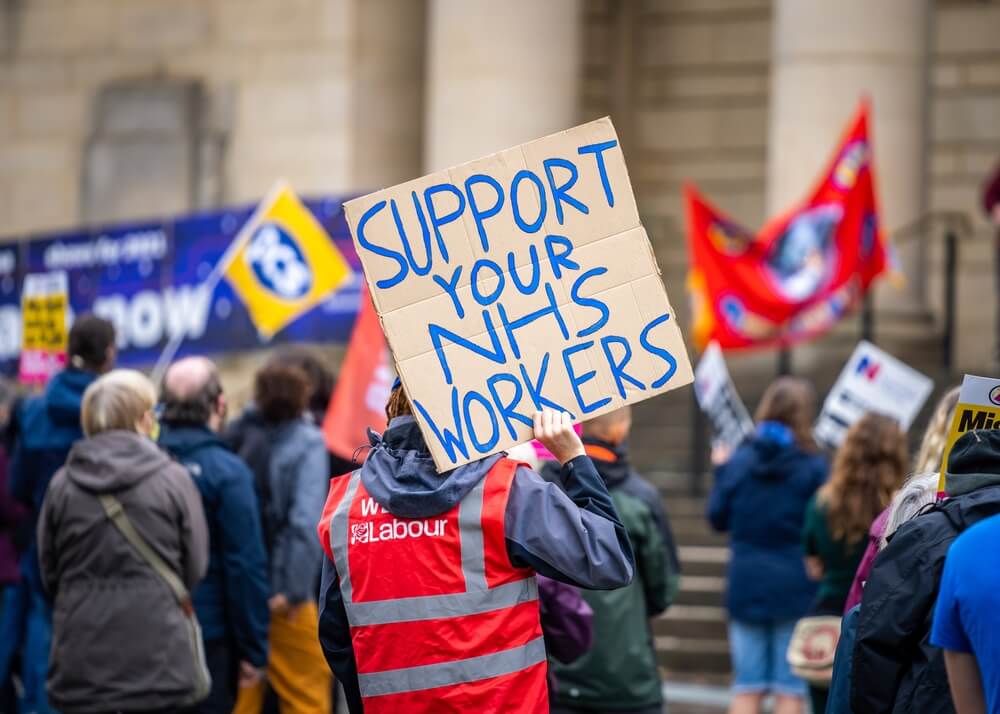

Many of those same health workers have since taken strike action to back increases in salaries they say have declined over the years in real terms. While the public has been broadly supportive, the stoppages have inevitably added to the existing pressures on the system.

Months-long waits for routine checks

Much of current dissatisfaction is based on prolonged waiting times rather than on standards of care. Latest statistics showed that 35 per cent of people had difficulty contacting their general practitioner, a four percentage point increase in half a year.

Amid frustration at months-long waits for routine checks or potentially life-saving treatment, 1-in-8 people last year opted to pay for private care, a third of them for the first time.

Research published by YouGov pollsters indicated an additional 1-in-4 would have done the same if they could have afforded it. More than half of those polled by YouGov said they paid in order to beat the queues, while only 15 per cent believed they would receive a better service in the private sector.

Healthcare campaigners warned that the figures exposed a worrying trend towards a two-tier system. Dr John Puntis, co-chair of Keep Our NHS Public, said private care was an option that excluded the majority of the population.

Since the pandemic, private companies have been aggressively marketing the health services they offer

Since the pandemic, private companies have been aggressively marketing the health services they offer

His campaign group notes that the current crisis is a relatively new phenomenon for an NHS that once topped the international rankings but fell behind due to a lack of investment.

It also challenges the perception that an increasing reliance on private companies, which by some calculations already receive almost a fifth of the NHS budget, would provide the cure. Much of the public money currently spent goes on services that are bought in from the private sector.

Since the pandemic, private companies have been aggressively marketing the health services they offer, while private investors, including at least one US insurance health insurance company, have been buying up local health practices previously run by small doctor partnerships.

They clearly see benefits in investing in the health sector, even if some politicians apparently do not.

The NHS has undergone innumerable reforms since its establishment in 1948, without abandoning its founding principles. Despite is current problems, there are probably zero votes to be gained by any politician daring to challenge its universal care model.

There is a growing prospect, however, that failure to address the current crisis will lead to the creeping privatisation of a still hallowed institution that was once regarded as a model for the rest of the world.